AP U.S. History adjusts to controversial changes

The Golden Protests

In a small town like Golden, Colorado school board meetings are usually nothing that citizens worry over. Some call them boring. They usually involve a simple discussion over any issues that the town is facing, followed by a search for solutions, and finally a period when parents are allowed to discuss any issues that they feel must be heard.

The Oct. 2, 2014 meeting, however, was very far from boring.

Karen Tumulty, a national political correspondent for The Washington Post, was in the Jefferson County area covering a Senate race when she came across the protests. Even though she does not usually cover education, Tumulty felt that this story had a political feel to it, and decided to look deeper into the events.

“I cover politics, and, more than anything, it was an interesting political story. It was the culture wars going to another level,” Tumulty said.

Perhaps the most striking feature of the protest at the school board meeting was the attendance. Even though she does not remember the exact number of people of the protest, Tumulty recalls people lining up, trying to get into the school board meeting. The surrounding blocks were filled with people trying to convince passersby to join their fight.

“There were a lot of people inside and outside the school board meeting. There was a long line of people trying to get in,” she said. “It was a massive community protest Friday along the county’s main boulevard.”

Hundreds stood on several street corners and along Golden roads telling people to show their support.

According to Tumulty, the protesters emotions were patent upon their faces. There were several parents of Jefferson County students who simply wanted to voice their concerns.

Up for debate were a series of controversial changes to the AP U.S. History curriculum, initiated by the College Board to allay the breakneck speed through which teachers had been racing through the copious tested material, that would focus the class on conflicts over power, what some claimed to be the darker, less triumphant moments of U.S. history. Major Untied States historical figures were not even mentioned by name. The recently elected school board in Jefferson County acted against these changes, decrying them for being unpolitical.

Board member Julie Williams said that the curriculum for Jefferson County would “present positive aspects of the United States and its heritage” and “promote citizenship, patriotism, essentials and benefits of the free enterprise system.” According to a document released by the Board Committee for Curriculum Review, “Materials should not encourage or condone civil disorder, social strife or disregard of the law. ”

Former candidate for the Republican presidential nominee, pediatric neurosurgeon Ben Carson, said that, with its focus on conflicts over power, “most people” who took the course “would be ready to sign up for ISIS.”

Yet with hundreds lining the street in protest of these changes — claiming that they are promoting censorship and one man waving a copy of George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984 — the plan seems to have backfired. One resident’s sign read, “Stop censoring our history,” and another said, “Our tax $ at work for secrecy, waste, disrespect.”

As a reporter for The Washington Post, Tumulty focused on the school board meeting, yet she was unable to overlook the people surrounding the building walls, the feelings evident on the faces of those within the town’s nine square miles.

“That day, in the area, you would drive around the city and on many street corners there would be parents waving signs protesting the school board actions,” Tumulty said.

In the meeting itself, several parents explained their concerns, detailing their reasons for protesting. Yet, just outside the door, the line stretched inexorably backward with more parents eager to get their word in, willing to wait as long as they needed before it was their turn.

Over the following months, several changes to the AP U.S. History curriculum did occur, not just in Jefferson County but across the entire country. The College Board considered the conservative reaction to its proposed curriculum and attempted to balance its curriculum.

In February 2015, Jefferson County officially dropped its plans to alter the AP U.S. History curriculum. On July 30, 2015, the College Board released its new AP U.S. History framework. The changes were “based on feedback gathered over the last year” and stress “a clearer and more balanced approach to the teaching of American history.”

While a number of people were satisfied by the revisions, the changes nevertheless have proved controversial to teachers and students across the nation, including those within the small town of Glen Rock, N.J.

Teaching the Change

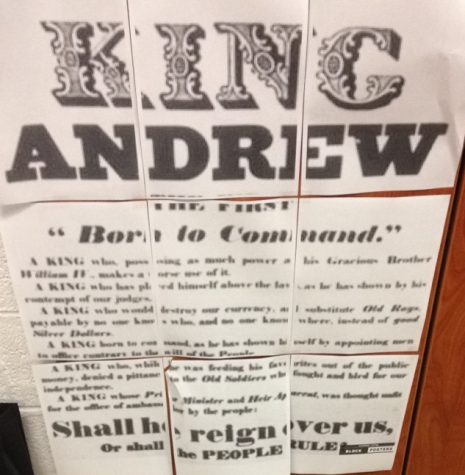

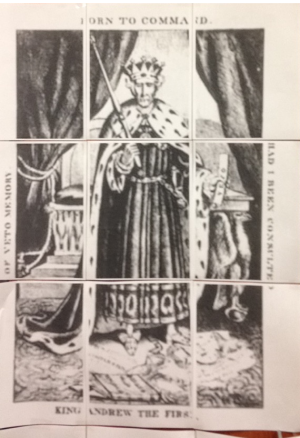

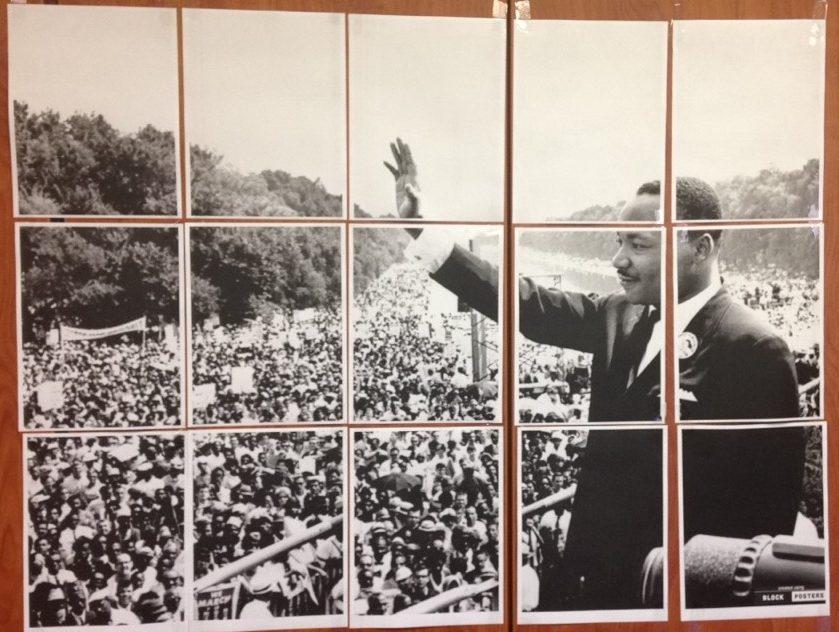

In Kathleen Walter’s classroom, posters circle the classroom walls: they depict propaganda from some of the nation’s best and worst moments. On the wall across from the window, the light shines on an over sized poster made by Walter herself: three sheets of paper long by five sheets of paper wide, it displays a famous photograph of Martin Luther King Jr. after delivering his “I Have a Dream” speech.

As Walter anxiously paces the classroom in early September 2015, her students begin to file in one by one to their first day of AP U.S. History. The students, however, are not the only ones with slight nerves entering the first day of the class. Walter spent time during her summer vacation reviewing the new curriculum for the 2015-2016 school year, a curriculum that had once again been changed by The College Board. These changes include the elimination of topics that used to be required. Now, Walter is given a broader spectrum through which the students must use their skills to analyze situations.

An example of this is the topic of the United States economy. Instead of teaching certain topics about the economic history of the United States, a teacher is allowed to teach the moments in our nation’s history that he or she feels is most significant.

The changes have also resulted in Walter having to create and grade her tests differently. With a broader topics instead of specific details, students have more options as to how they will answer certain questions. As a result, Walter has had to create tests that allow students to give their own answer, instead of guiding them to write one specific and correct answer.

“They ask for short answer questions. They’ll give you a document and say ‘Give me one example of…’ There could be eight correct answers to that,” said Walter, explaining the breadth of answers this new curriculum permits.

Advanced Stress

As Walter sits in her room, she copes with the various stressors that being a teacher of an advanced placement course entails. The numerous tests, quizzes, and essays that she must grade keep her constantly busy. Walter must also keep on top of the curriculum changes.

Christopher Pohlman, Honors U.S. History I teacher and head of the Social Studies Department, believes that the changes in the curriculum has created a stressful atmosphere for the teachers.

“Teaching an AP course is stressful enough and changing the curriculum adds stress to the shoulders of those that are responsible for teaching these upper level courses,” Pohlman said. “These changes to the program have required a complete overhaul to the way that the courses themselves are taught.”

Part of the controversy about these changes was the way in which they were implemented. The changes came suddenly and with minimal warning. As a result, teachers of AP U.S. History were forced to learn the changes and implement them over the summer in order to prepare for the upcoming school year.

“In my opinion, and it is just that, an opinion, changes to the curriculum should have been phased in over time and not just made overnight,” Pohlman said.

As the teacher of an Honors US History class, Pohlman’s job is to prepare the students who are interested in taking AP US History for the following year. As a result, these changes have caused his teaching plans to change. Although Pohlman’s curriculum has not changed, the way he teaches each section has to be altered as a result of the College Board changes.

“The content of the course remains the same, none of that is changing,” Pohlman said. “What I have done is made primary source analysis and primary source more of a central focus of the class.”

Primary documents have become a major component of the new AP U.S. History curriculum. Previously, the documents only showed up occasionally throughout the year. They are now involved in almost every lesson taught and are on almost all large exams throughout the year.

“When documents are being analyzed, or certain topics are being covered, I try to emphasize the time period as a whole,” Pohlman said.

With the changes in the curriculum comes more stress, especially on the students. Students spend hours each night changing their study habits to adapt to the protean AP test.

As students enter the media center from the cold of the school courtyard this winter, they enter possibly the most quietly active room in the building. To the right, computers line-up on the walls. To the left, newspapers and magazines fill the shelves from as low as the floor to where only the tallest students could reach. Beyond another row of computers, tables full of students study frantically for their midterm upcoming exams.

Among these students is James Sommers, junior, who tries to cram in as much information from his AP U.S. History textbook as possible before he must finish the rest at home. Despite the long time he has spent studying, there is still more information.

Race movements throughout American history serve as significant parts of the AP US History curriculum.

“We don’t have enough time,” Sommers said. “There are too many things that must be included in the essays for all of them to be done very well. You can’t spend too much time planning on one part of the essay or you won’t have enough time for the other parts.”

Ignoring the rigors of the multiple choice, short answer and essay questions, the biggest problem for students may lie in the primary source document based questions, or DBQs. A DBQ answer requires interpretation of the source, followed by a question that asks the meaning behind the document.

“They are asking their kids to write this huge essay based on documents,” Walter said. “They’re asking them to do too much in forty-five minutes.”

Although many students find these primary documents long and tedious, it is essential to practice reading them prior to taking the AP U.S. History exam, according to Sommers. Once a student reaches the high level, a large part of his or her grade depends on the ability to read these primary sources and answer the questions that follow.

“It helps a lot to prepare us for the AP test and allows us to better grasp the material,” Sommers said.

Reviewing the Past

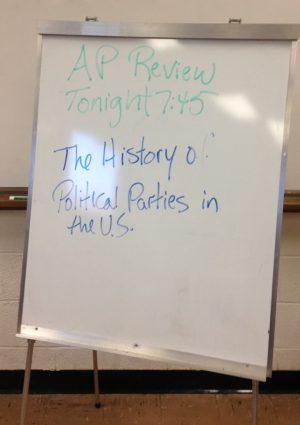

At night, after the sun has set and only one door at Glen Rock High School is open, AP U.S. History students file into Walter’s classroom. As they enter the door, they walk past a whiteboard set on an easel outside the classroom door. The sign reads, “AP Review Tonight 7:45. The History of Political Parties in the U.S.”

As students begin to sit down and get settled, Walter begins the session: a class held after school specifically to cover additional material for the AP exam.

All AP courses are difficult. However, there is one particularity that sets AP U.S. History apart from the rest: students must not only retain what they learn during the current year, but they must also remember what has been learned in past years.

At Glen Rock High School, students spend one year learning U.S. History I, followed by U.S. History II the next year. For students taking Honors or College Prep US History II, the only material that they need to remember is that which was learned during the current year. This, however, is not the case for those taking the Advanced Placement Course.

The AP U.S. History test in May includes material from the U.S. History I and II curriculum. This forces students and teachers to spend extra time reviewing material from prior years.

Students and teachers have spent several nights this year reviewing U.S. History 1’s curriculum.

According to Walter, this long test contradicts the goal that the College Board has of making AP courses as similar as possible to a college course.

“The AP is supposed to be like a college course,” Walter said. “I would actually like to see a AP U.S. I or an AP U.S. II test because no college course that I know of goes from 1492 until, believe it or not, we have to get up to 2005.”

This time period of over 500 years contains a significant amount of information. Much of this information is covered in the hour-long class periods, yet, due to sheer volume, some students must learn on their own time. To account for this, Walter puts in extra hours to help students review curriculum that she is not officially responsible for.

“There’s 300,000 kids who take it because it’s one of the most accessible ones,” she said.

Walter explained that the AP appeals to students who think “I’m not going to take AP Physics. I’m not going to take AP Calc, but APUSH is a skill that I can definitely do, because I can read and just improve my skills.”

The solution, Walter says, is simple.

“I would just like them to split it up into two, just like they split up physics into two.”

With only a month left to study everything from both years when he was interviewed, junior David Belkin felt unprepared for the exam.

“I’ll have to study more on my own,” Belkin said.

Unpatriotic

Follow the Golden protests, the College Board decided to make perhaps the biggest change of all: they would concede to the conservative movement and make the curriculum more “patriotic” by shifting the focus from conflicts over power in the nation’s history to focus more of the country’s brighter moments.

Pohlman believes that learning our country’s accomplishments alone does not teach enough, if anything at all.

“Lessons are learned through failure,” Pohlman said. “If all we learn are our successes and the good things that we have accomplished, then what have we learned?”

Pohlman also believes that, even when students are learning about America’s missteps, this does not make the school or the curriculum unpatriotic. It rather creates a desire for a successful future.

“Does that then mean that we should take a negative view of our own history?” he asked. “No, of course not, but we should not just be blinded by our successes.”

Some people blame the College Board for stirring up discord, specifically in regards to race relations.

“That’s not one of our prouder moments,” said Walter in regards to the history of U.S. racial discrimination. “Some people are criticizing the College Board for criticizing the problems that we have with race, rather than the triumphs that we’ve had with providing people with greater rights.”

Walter feels that the College Board was a victim of misunderstanding, saying that generalizing the curriculum has allowed some people to feel that they are missing out on the greatest moments and people of the U.S.

“The College Board is highly criticized for not being patriotic enough,” Walter said. “Because the College Board no longer provides a list of specific terms to fill in for the curriculum, a lot of people were angry because they no longer saw George Washington’s name on there, and they actually accused the College Board of being unpatriotic. ‘How can you not teach George Washington?’ And then the College Board argued back, ‘Of course we’re teaching George Washington, but it’s the school board’s choice of how you fill in.’”

Walter believes that the problems should not only be taught, but students should learn how to fix them, as well.

“Personally, I believe that we should teach it as a narrative flow,” Walter said. “We need to teach our students how to be critical thinkers.”

As problem solving is taught in other subjects, Walter feels that U.S. history is not exception. She feels that our nation has had enough problems that students should be able to figure out how to solve certain ones.

“I think that American History is a really good example, a history filled with problems, and how we can solve these problems,” Walter said.

Pohlman and Walter both believe that history should be taught for what it is: a path of imperfections in which students must learn to prepare for the future.

“I do think we need to teach the positives and the negatives and see it as a constant work in progress,” Walter said.

Walter believes that some of our proudest moments, such as the Constitutional Convention, can also be criticized and analyzed for its failures.

David Belkin believes that solely teaching the positive aspects of history does not only prevent students from preparing for the future, but it does give them a slanted view.

“It’s good to see the negatives and the positives,” Belkin said. “Otherwise, our views would be too biased. We should see the full story and not chose bits and pieces.”

Colin Morrow is a senior at Glen Rock High School. He plays hockey and baseball and enjoys writing about sports. This is his third year of journalism....