1940: From Glen Rock to War

May 23, 2016

It was 1940:

The United States was emerging from the Great Depression.

Germany had captured much of Europe.

The Japanese Army was marching through China.

London was being bombed nightly.

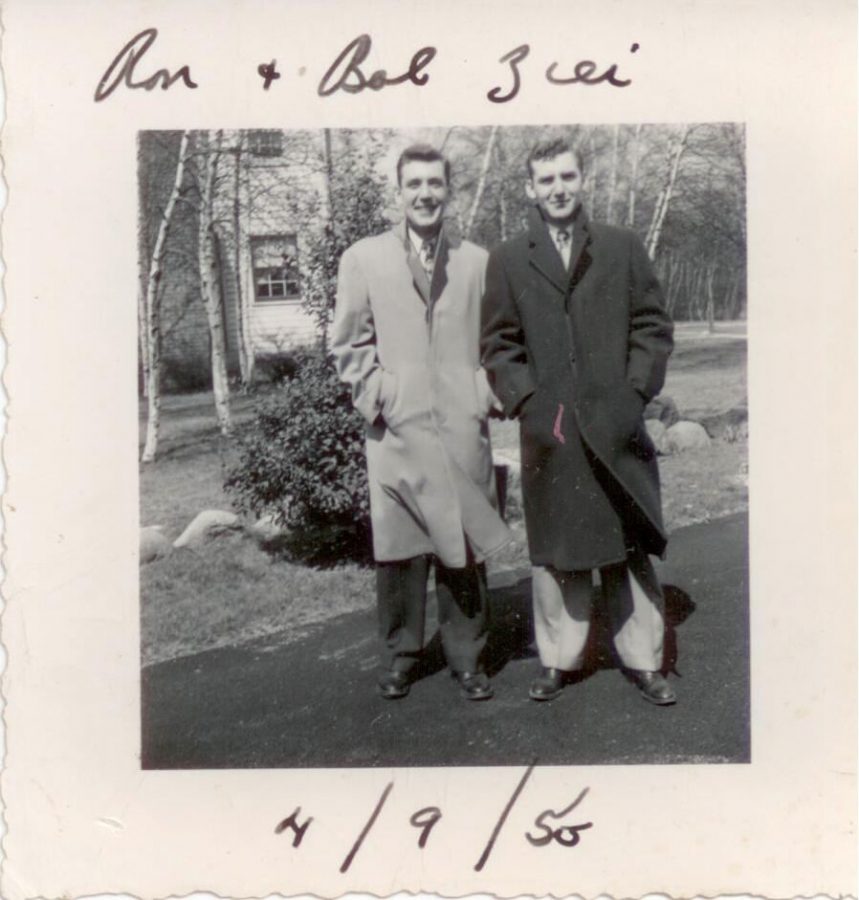

As World War II seemed to be tearing the world apart, Ronald and Ethel Zier were searching for home to raise their two boys in. Moving from Jersey City, the couple had been to a dozen places before deciding on a small, friendly town with good schools and easy transportation, Glen Rock, NJ.

Somewhere to grow up

The family hired a builder, Fred Davenport, to build a brick colonial home on a quarter acre of farmland. The house consisted of three bedrooms, two bathrooms, a living room, dining room, kitchen, a screened porch, a deck, and an attached garage for a total price of $7,500. The house was built on a newly developed Waldron Avenue, which was yet to be paved, allowing for many mud puddles to jump around in. Behind the house was an abandoned apple orchard and a chicken farm where the neighborhood kids would have apple fights or used the fruit as baseballs. That land would later become St. Catherine’s Church in 1953.

The Zier family was able to move into their newly built home in May of 1941, Ron Zier was ten and his brother, Bob Zier was nine. This would be the home in which the boys would listen to a Giants game over the radio and hear a news bulletin announce that Japanese planes had bombed Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. This would be the home in which the Zier family would grow string beans, corn, and tomatoes in their Victory Garden in efforts to increase food supply during the war. This would be the home in which the Zier brothers grew up.

Coming from a rural city almost 30 miles away, Glen Rock was a completely different world for the brothers. Instead of chasing each other through alleys and over fences, they were now surrounded by acres of farmland. Two working dairy farms on the east side of Harristown Road provided space for football games, and idle trolley lines were makeshift baseball fields. Both of the boys went to Central Elementary School for fifth and sixth grades.

Downtown Glen Rock was an important feature of the town, consisting of roughly two dozen stores, among them were Bill Francis’s delicatessen, Kaver’s and Newman’s candy stores, and Bill Merry’s hardware store. Other staples of the town still stand today, with a few distinct differences. Rock Ridge Pharmacy was then called the Village Pharmacy, Kilroy’s Supermarket stood on Maple Avenue rather than Rock Road, and the corner Bank of America was not always colored pink.

Ron Zier is able to recall his childhood memories in detail, including the geographical layout of Glen Rock, street names and addresses, however his strongest memories of the town are of the people who lived there.

“Middle class achievers who were proud to provide their kids a decent education along with acres of open space to wander through,” Zier said.

Glen Rock Junior High Graduating class of 1945. Bob Zier pictured standing third row, fourth from the left.

The homefront

On a Sunday afternoon around 1:30, December 7, 1941 to be exact, the Zier family was sitting around the kitchen table eating lunch while listening to the baseball Giants play the Brooklyn Dodgers over a live radio broadcast when an announcement interrupted the football game.

“We interrupt this broadcast to bring you a special news bulletin; The War Department reports that unidentified planes have attacked naval installations at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Stay tuned for further developments.”

The boy’s father, Ronald Zier, immediately exclaimed, “This is war!” He worried for his brother, George Zier, who was stationed as a Coast Artillery member at Pearl Harbor. The planes were identified as Japanese within the hour, and that same week, Germany had declared war against the United States.

George Zier fortunately wasn’t hurt, and his gun crew managed to get a reported hit on a Japanese plane. Just as Ron Zier had exclaimed, this was war.

With war brought rations. The family had a Victory Garden for three years.

“I remember picking 80 tomatoes one day,” Zier said. Other products like meat, butter, eggs, even gasoline and tires were rationed. The neighborhood was in a semi-blackout mode, and no outdoor lights were permitted. The once illuminated New York City skyline went dark, and cars had a portion of their headlights covered in fear of ships casting a silhouette against the skyline, making them easy targets for German subs.

The family began saving cans, tin foil, bacon grease, and any scrap metal for the war effort. Ronald Zier Sr. had become an air raid warren for the area of Glen Rock.

By 1942, Ron Zier Jr. had entered the seventh grade and was enrolled in Glen Rock Junior High School. He walked half a mile along Harristown Road to school every morning, passing two dairy farms on his way.

Some of Zier’s most prominent memories of Junior High mark significant days in American history. On June 6, 1944, just as he had been during the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Zier listened to radio reports of the D-Day invasion of Europe. He and his entire class listened to the radio at 9 in the morning on May 8, 1945 to listen for official reports of the end of the war. The voice of Winston Churchill addressed the classroom, and the world, about the cessation of hostilities. School that day was closed.

On August 7, 1945, a nuclear bomb was dropped. The bomb that was dropped half way across the world ended the war and is largely considered the most important event of the 20th century.

“[Hiroshima] forever changed not only our concepts of war, but also our understanding of nuclear energy and its availability to mankind as fossil fuels fade,” Zier said. Word of the explosion was brought by the six o’clock evening news into the Zier household that night. Ron Zier remembers feeling ambiguous about the attack. The bomb successfully eliminated an entire enemy city, but also devastated an entire city of people and threatened the future of nucleus wars.

Less than a week later, August 15, 1945 was a celebration in Glen Rock. The Ziers celebrated the discharge of George Zier and the end of war.

Go Maroons

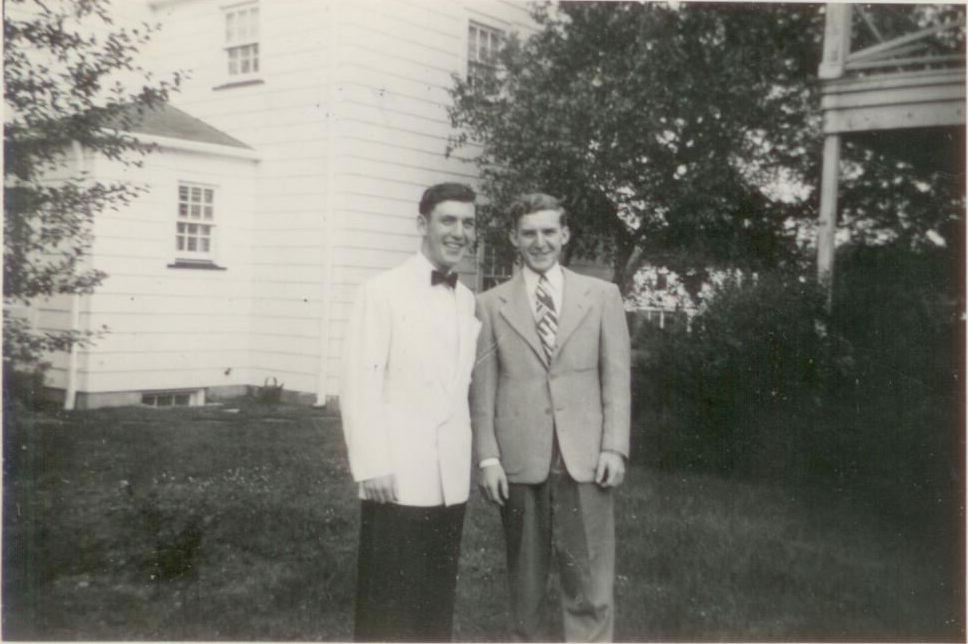

Ron Zier attended Ridgewood High School, as did most of his classmates as Glen Rock High School, was nonexistent until 1956. Some of Ron’s favorite classes involved English, Public Speaking, and Writing. In his Public Speaking class, students would pick a topic from a hat to discuss for three minutes in front of the class. Ron Zier also served on student council and pitched for the baseball team.

In the mornings, he either rode his bike to school or got a ride in someone else’s car. The country was free from gas rations, but Ron Zier wasn’t able to drive until just before his graduation in 1948. On the night of their graduation, Ron and several friends went into New York and walked around Times Square. “Because that’s what we thought you did,” said Zier.

High school memories for Zier consist of driving lessons, snow shoveling, and watching the 1947 World Series on their first television set. The boys ran home from school, still unable to drive, in hopes to see the Yankees play the Dodgers in the last few innings.

Of the few fights Ron Zier remembers having with his brother, the root of the arguments seemed to be the outcomes baseball games. Boxing lessons from their father came in handy on these occasions.

Life overseas

Ron Zier (Right) pictured at his locale near the town of Chorwon, Korea. On his left, Commander Roy Huff is pictured.

After graduating from Notre Dame University, Ron Zier immediately enlisted in the army and took naval aviation exams in order to complete his military service.

He passed his written exam, however, he mysteriously failed his hearing test, despite having perfect hearing. The idea of landing a jet going 150 miles an hour never really appealed to him.

Despite failing his exams, Ron Zier spent eight weeks at Fort Custer in Battle Creek, Michigan to take a basic training course designed for “non-combatants.” He then went to Officer’s Candidate School to serve as an officer in management and distribution of equipment.

Regardless of his best efforts to stay off the battlefield, in late 1952 Ron Zier was selected to be an infantry platoon leader in Korea. During his interview, Zier distinctly remembers telling the colonels that he couldn’t possibly imagine shooting anyone.

“Those gentlemen were so impressed by my aplomb that my orders sending me to Korea came within 24 hours. Who said the military had no sense of humor?” Zier said.

On Jan. 19, 1953, Ron Zier left for Korea. He was aboard a 17,000 ton merchant ship named the General Funston. The ship had been refitted as a troop carrier, making for very little space. Over the nineteen days it took to sail across the Pacific Ocean, Ron Zier worked as an editor for the the ship’s newspaper, strategically avoiding kitchen duty in an effort to avoid seasickness. After a stop in Japan, the General Funston docked in Inchon, Korea on February 13, 1953. The troops traveled to the headquarters of the Second Infantry Division by train. At every stop, orphan beggars tried to get as close as they could to the train to feel its warmth, to beg for food, or money. When the men arrived at the headquarters, one could hear the sounds artillery and tracer bullet trajectories overhead.

Because he had writing and typing skills, Ron Zier spent sixteen months with a headquarters that handled writing medal citations and casualty reports. When he was considered to be in a combat zone, his pay was raised to one hundred dollars a month.

Although he was of a non-combatant status, Zier also handled his share of guard duty on the 2 a.m. shift, sometimes in negative 20 degree weather. Every snap of a twig or crack of ice made Zier jump with anxiety. Being alone proved to be paradoxically both alarming and assuring.

One evening, on guard duty, Zier was walking toward the farthest post, when a tent flap flew open, casting a beam of light in his direction. Seeing Zier and mistaking him for an enemy, a presumably drunk UN soldier fired his carbine gun at him. Zier dove as the bullets flew just above his head, hitting the ground chin first. He dove as soon as he saw the light, and his only injury came from the impact of his fall.

Camp was located a half mile behind the battle line, right next to the Chorwon River, which served as a bathing facility and a recreational spot during the summer months. They lived in eight-man tents with a single light bulb in the center, and coal burning stove for heat.There was an 11 p.m. lights out along with a 6 a.m. wake up call In the winter, soldiers would take lukewarm showers in a tent with oil stoves. Some soldiers would make themselves useful by doing laundry or other household chores, granting them a few extra dollars along with a guarantee of three meals a day. When it rained, a river would run through their tents, but the men always had decent food and warm clothes.

Life in Korea, at least for Ron Zier, wasn’t horrible. There was a certain camaraderie among the soldiers. Zier himself started a tradition among the men. They would pass around a St. Olaf College t-shirt to the next person who was being rotated out of Korea and heading home. Possession of the shirt meant you were a “short timer”. The men celebrated Christmas of 1953 together. They cut down a small evergreen and decorated it themselves, and on Christmas Eve they traveled twenty miles from camp to attend a midnight mass, given by Francis Cardinal Spellman, New York’s Archbishop at the time.

Daily casualty reports were given to the soldiers and helicopters flew above them carrying wounded soldiers to Mobile a Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) nearby. Everyone carried a weapon, maybe two, wherever they went. Even to mass. One Sunday afternoon, a shackled prisoner armed with a rifle stopped the service and demanded that the priest help release him. He pleaded louder and louder, and threatened to shoot everyone, but no one moved. The priest finished the mass, and afterwards talked to the prisoner, taking the rifle from him.

Later in his military career, Ron Zier was chosen to write speeches that would be delivered to Army personnel stationed in Korea. The pieces were for General Maxwell Taylor, the commander of all Far-East Forces acclaimed

In April of 1954, Ron Zier received the Bronze Star. The medal was given by the Commanding General in front of the troops. The ceremony was completed by the division band playing the national anthem as the flag being lowered. That same year, Zier left the Army in Korea and took a ten day voyage to Seattle. After his discharge, Zier was able to fly home Glen Rock and put his adolescence and army days behind him.

“I had just turned 23. It was time to get on with the next act, start a new adventure,” said Zier.

A sort of homecoming

Jump forward to the year 1957. By this time, Ron Zier was working as a public relations associate for Lederle Laboratories. He was 26, married to Dot Zier, and the two rented a one- bedroom apartment in Spring Valley for $75 a month.

The apartment was suitable for the two of them, but not for three. Dot became pregnant with their first son, Edward, and Dot and Ron began a search for a house. After a few months of hunting, Mr. And Mrs. Zier moved into their home on Greenway Road in Glen Rock. The total cost of the colonial home was $19,200; and the two would write out a monthly mortgage check for $67.84 for the next twelve years.

Every morning, Ron Zier would commute to work in a white Chevrolet sedan and would spend $2.00 a week on gas. Approximately ten gallons a week at 20 cents a gallon.

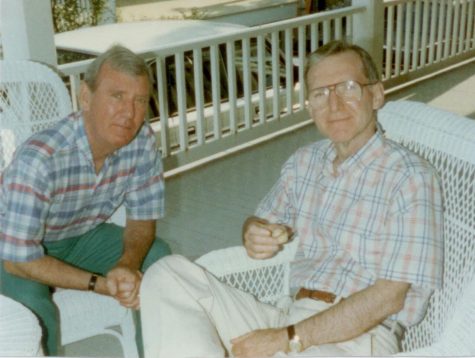

By 1960, Ron and Dot Zier had two sons, Edward and Ron Jr., and Bob Zier had completed his Army service in Germany as a crewman on a rocket system. Bob traveled Europe and visited Amsterdam, London and Paris on his weekend leaves. While in London, Bob Zier was standing outside of Buckingham Palace when he ran into two of his classmates from Ridgewood High School Class of 1949.

In 1956, Bob began working as an advertising manager a Swedish steel manufacturer called Sandvik. He worked in Fair Lawn, and it was there where he met Patricia Margaret Kenney. On April 19, 1958 the two were married. The ceremony was held at Holy Trinity Church in Hackensack, and Ron Zier served as the best man. The newly married Bob and Pat Zier moved to a New England Style home on Oakwood Drive in Wyckoff. This was the home that the couple would raise their two daughters and spend the rest of their lives in.

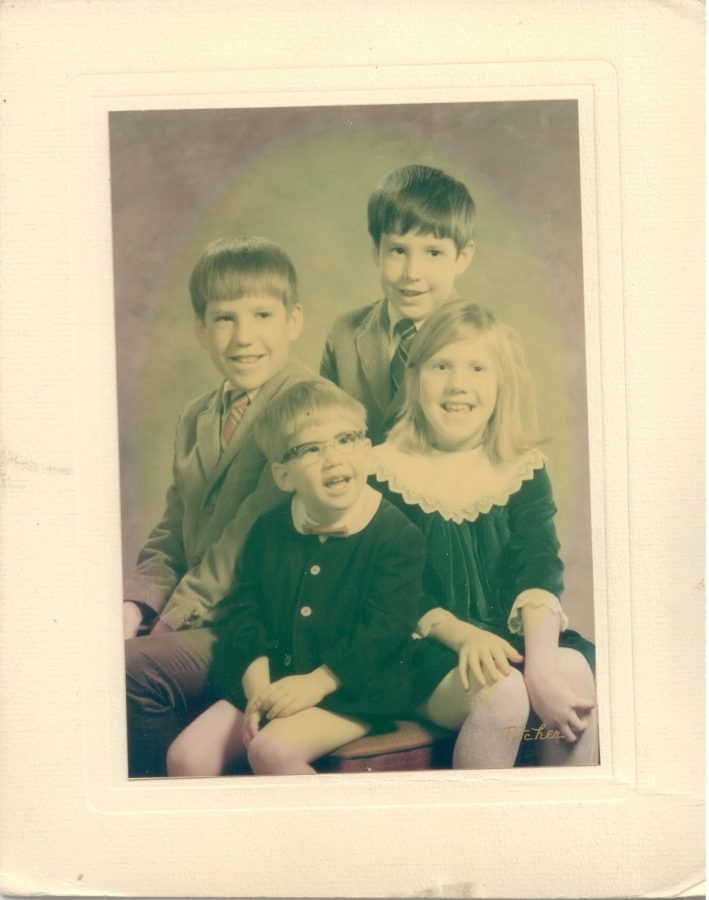

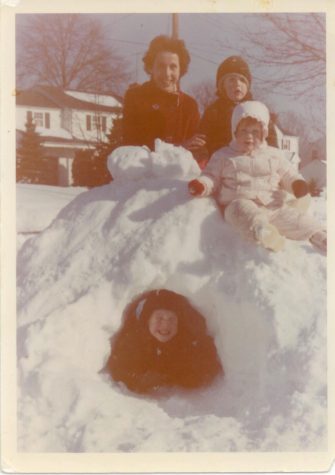

Ed, Ron Jr, Julie, and Jim Zier all grew up in Glen Rock, as their father did, in their home on Greenway Road.

The children would play outside all day in the warmer months, and build igloos and go sledding in the winter. “There was more snow back then, I swear,” said Julie Kiess (nee Zier).

The Glen Rock Pool, built in the late 50s, was equipped with a high and low dive, but no slide.

“People were always more formal,” Ms Kiess said. She claims that children were more protected when she was growing up.

Her mother, Dot Zier, once hid a Barbie doll from the children because she believed it was inappropriate for them to be playing with a doll in a bathing suit. That didn’t stop them from finding the doll, and marrying her to a GI Joe doll. The “Zier bunch” would play with neighborhood kids in their backyards all day, playing games like hide n’ go seek and ghost in the graveyard.

“You knew all your neighbors, you would hang out on your stoop, people would walk by and you’d talk… I don’t think it’s like that today,” Kiess said.

Like their father and uncle, Glen Rock Little League Baseball was a prevalent part of the boy’s childhoods. Teams made up of 10 and 11 year old boys would compete at the Maple Avenue fields that still exist today. The teams were sponsored by local businesses like Rock Ridge Pharmacy, Glen Rock Hardware, Herold’s Farm, and Beekmans to name a few.

Today, Zier lives in Wyckoff, but relatives of Ron Zier still live in Glen Rock today. The town has provided a backdrop not only to his childhood in the 1940s, but his children’s.

“Good stuff. I remember it fondly. I grew up there,” said Zier.