Glen Rock reporter anchors Emmy-nominated program

May 4, 2016

The Japanese government doesn’t want anyone to know the story that Glen Rock resident Minnie Roh has told in her Emmy-nominated story.

It has denied its involvement, claimed that the women were ‘volunteers,’ and attempted to remove passages from American textbooks.

The Japanese government doesn’t want anyone to know about its sex slaves during World War II, even today, 70 years after the fact.

But Minnie Roh doesn’t care what the Japanese government wants. She has a job to do: she’s going to tell the truth and spread awareness.

She’s a reporter.

A Japanese military official salutes during World War II in this clip Roh collated for her Comfort Women segment.

Comfort Women

Minnie Roh grew up in Korea, yet she never learned about Comfort Women in school. She learned about them at home as a little girl from her mother.

For Korean parents, it was the type of cautionary tale they would tell their children when they asked to go out at night: a story full of evil men.

“Annie was just like you,” one mother might say to her daughter. “She lived down the street from me. We used to wander into our neighbor’s garden and steal blackberries.”

The young girl, listening, nods her head, thinking this would be just another story about her mother’s childhood that she has already heard all too many times before.

“Then,” the mother says as she looks away from the pot she is stirring to look her daughter directly in the eye, “she was taken.”

The name ‘comfort women’ is a euphemism on multiple levels: first, it downplays the torturous existence that these abducted women survived; secondly, many of them were not yet women — they were girls, 12, 13, or 14 years old, snatched on their way home from the market or walking to a neighbor’s house. The original word is derived from the Japanese ianfu, a socially acceptable way to refer to a military prostitute.

What distinguishes the Korean mother’s tale from similar horror stories involving boogeymen, though, is that her story is true.

The Japanese occupation of Korea began in 1910, over three decades before the official start of World War II, which would signify the end of the hegemony.

During World War II, the Japanese Empire turned particularly repugnant. It exploited the land for food, leaving the native Koreans in squalor. It forced the Korean men into hard labor, forcing them to work for the Japanese military machine. It stole women from their homes either by force or fallacious promises of a better life, locking them into military brothels and forcing them to sexually serve sometimes 50 men in a single day.

This is where the cautionary tale that the mother tells her daughter comes from, a history of terror and violence that still keeps her up at night.

Yet the girl, dressed in a white shirt and a dark blue vest, says to her mother, innocently: “Who still gets kidnapped? That was years ago. It doesn’t happen anymore.”

And that was that — with a single dismissal, the story of Comfort Women was swept under the rug. Somewhere between 10,000 to 200,000 women’s stories casually ignored because, of course, it could never happen again.

For people like Minnie Roh who know the story, the biggest fears are ignoring and forgetting.

“Going back and forth to Korea a lot, you hear about these rallies and these old ladies trying to get justice,” Minnie Roh said. “It is one of those things that are kind of just there in my stratosphere.”

What Minnie refers to is how time and distance gradually blunt the trauma suffered by these Korean women, smearing them from the annals of history.

Unfortunately, this is the way that the Japanese government wants it.

When Emperor Hirohito of the former Japanese Empire surrendered to the Allies on August 15, 1945, the Japanese quickly went to work — the Japanese government, despite its capitulation, had already seen the remnants of the Nazi party captured and imprisoned for its crimes and knew of the impending Nuremberg trials that would occur beginning in November.

Yet, oddly enough, despite atrocities committed by the Japanese government in places such as Nanking and the Bataan Peninsula, the Tokyo War Crimes Trials were of a significantly lesser degree than Germany’s legal punishment.

The reason may lay in a single word: fire.

Surrendering on their own terms after witnessing the mammoth power of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, the Japanese had already implemented plans to dispose of evidence before the Allies flooded the Japanese mainland, which, unlike Germany, had not yet been penetrated by Allied foot soldiers. The fact that Allied soldiers already possessed areas of Germany when the Nazi party surrendered preserved evidence that otherwise could have been tampered with; in Japan, this was not the case.

Many of Japan’s damning files were burned, shredded, or otherwise destroyed.

Apocryphal accounts were told by liberated soldiers, Japanese military officials confessed to heinous acts, but nonetheless many stories went untold, buried with the bones of those lost and gradually blanched by the slow tide of history.

The story of the comfort women is one such story, often overshadowed by the explosive battles, big bombs, and heroic actions of the soldiers during the war. Insofar as the story of the comfort women go, it has often been overlooked.

For most Americans, the story of comfort women is alien and disturbing: these were young women who were taken from their homes, given false promises of work or food, only to be deposited into the dank corner of a “comfort station” where they were repeatedly raped and beaten by their captives.

They were not all Korean, either. They came from China, the Philippines, Taiwan, Burma, Indonesia, and even Australia, among others.

Minnie Roh heard these stories when she was a child. Then, when she moved to the United States, she mostly stopped hearing them. The protests of the comfort women became the backdrop to the weekly news; they became a fixture of nature, a sad fact that was in the past now.

In Glen Rock High School, one of the top achieving public schools in New Jersey, most students had never learned about comfort women.

The issue was only addressed in few American textbooks. Yet that wasn’t enough for Japan.

According to The Japan Times, 50 scholars from Japan demanded, in a December 2015 letter to Perspectives on History (a publication by the American Historical Association), that McGraw-Hill remove a section from its Traditions and Encounters textbook that explained the existence of comfort women during World War II. It marked the first time that a Japanese entity had attempted to censor information regarding comfort women outside of its own borders, which it has already done completely.

For all intents and purposes, it seemed as if Japan might be winning in its concerted efforts to whitewash comfort women from history; fewer and fewer people knew about the atrocities and even a smaller amount told their legacy.

Then, the women started dying.

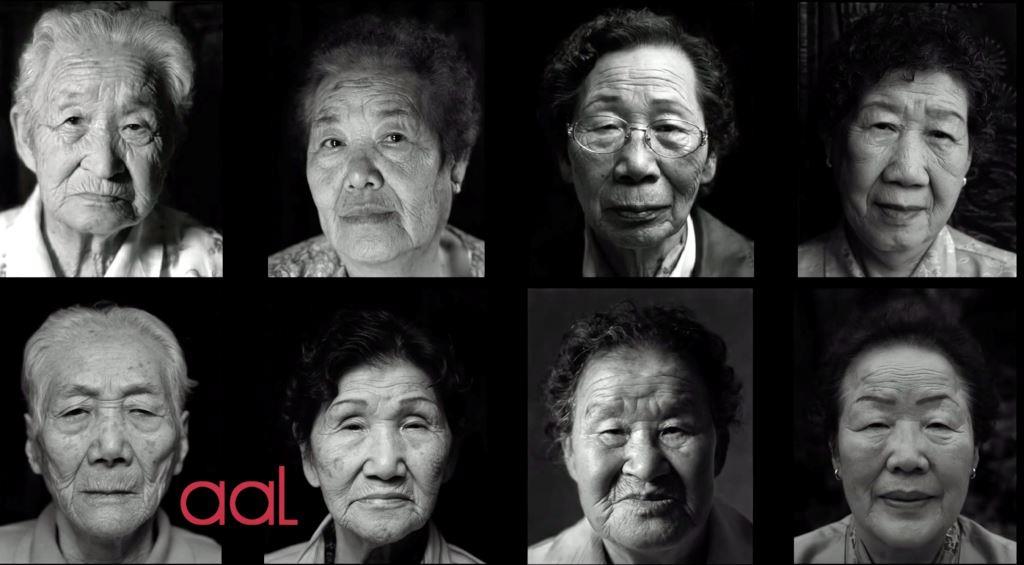

Their numbers dwindling, Minnie Roh knew she had to act quickly. She had to capture the story before it was too late, before the last living witnesses of this horror story vanished, just like the Japanese government had wanted it to be.

All of the Comfort Women live in Korea, but only about 8 of them live in the House of Sharing.

Crafting the story

The Japanese government acknowledges that comfort stations existed, but they don’t acknowledge that they had any part in it.

The Japanese say the stations were run by outside sex traffickers who were the ones who kidnapped the women and brought them over to serve.

Yet women from all over the world, from the Philippines to Vietnam to Korea, who have no contact with each other, are all telling the same story.

Are the women or the Japanese government lying? How can there be a mass lying going on between all these women?

Minnie Roh took it upon herself to tell the stories of these women’s fight for recognition.

She pitched the idea of Comfort Women as one of the many Korean stories she brings up at one of the Asian American Life weekly meetings. Through her research, she found an internship program at the Queensboro College, which eventually became her American hook.

“It would be a little bit of history and we can educate the people about this internship,” Roh said. “So I had this half-baked idea and it all of a sudden came together and I was like ‘Wow, that’s great.’”

Unlike any of the segments she has produced in the past for Asian American Life, her main interviews were done through Skype because the Comfort Women live in Korea.

Roh found it difficult to relate and connect with the women through the screen. She was missing the personal touch.

“There is something about being together in a room and feeding off people’s body language,” Roh explained. “There are ways you can interview and get people to say things they wouldn’t ordinarily say. That was very challenging because it was very static.”

Some of the Comfort Women live together in a house called “The House of Sharing.” The home exists because some of the women have been ostracized from their families after they opened up about their pasts.

“But Korea being such a family oriented nation, I really didn’t think they would get shunned by their families,” Roh said. “That was a big surprise to me.”

The women were very scattered and not organized for news purposes, so Roh depended on the Queensboro relationship with the House of Sharing to reach out to the women.

““It was a very difficult story to book, produce. Logistically, it was a nightmare for the Korea part. But it all worked out,” Roh explained.

The Queensboro internship program has a library of all their Skype interviews with the Comfort Women and a book with information. Roh watched, listened and read through all of the Comfort Women’s interviews and dossiers and picked the ones with the most interesting stores.

She identified about seven women, but only two of them were willing to speak. Roh interviewed You Hee-Nam and Lee Ok-Sun over Skype for about an hour and a half each in Korean.

The Comfort Women interviewed were in their 80s and 90s, so they had difficulties with the technology.

“I really only need one good interview, but two is good because in a story like this, you need different voices,” Roh said. “I was able to bring in the other voices on my own. I just needed someone to actually be the talker.”

Roh described both interviews as equally impactful because their stories were so similar yet so different. Each Comfort Women went through torture in different locations.

After the interviews, Roh had about three hours of information that she had to pare down to 11 minutes. She also had to include the history of Comfort Women and the information about the Queensboro internship. Her segment aired on May 1, 2015.

“You only get the surface of the horrors,” Roh said. “I tried really hard to do my best to depict how horrible it really was, but I didn’t even do it justice.”

A follow-up was created for Roh’s segment in terms of the agreement and deal that was brokered between the Prime Minister of Japan and the Prime Minister of Korea.

“You do have to repeat and retell the significance of the story because you always have to imagine when you are speaker to any reader or viewer online you cannot assume that they know what a Comfort Woman is,” Lord explained. “So she had to retell that. That was actually the news that broke. There is not much wiggle room for that.”

Roh’s story highlights the history, facts and emotions of Comfort Women, which has never been showcased before.

“From the feedback I have gotten, everyone has said people who aren’t even working as lobbyists have all said to me this is the most comprehensive story we have ever seen done about the Comfort Women even of all of our years doing reports with local stations,” Roh said, reflecting on her work. “Nobody has ever covered it quite like this. For me, that was really comforting to know and it was a big compliment that I can help.”

Asian American Life submitted Roh’s clip for a regional Emmy nomination and it received the nomination under the Historical/Cultural: Program Feature/Segment category.

“Minnie always brings to our show ideas that are not necessarily discussed in mainstream media and she is a real go-getter,” Lord said. “So it was no surprise that after being one year on our show that she was nominated for an Emmy.”

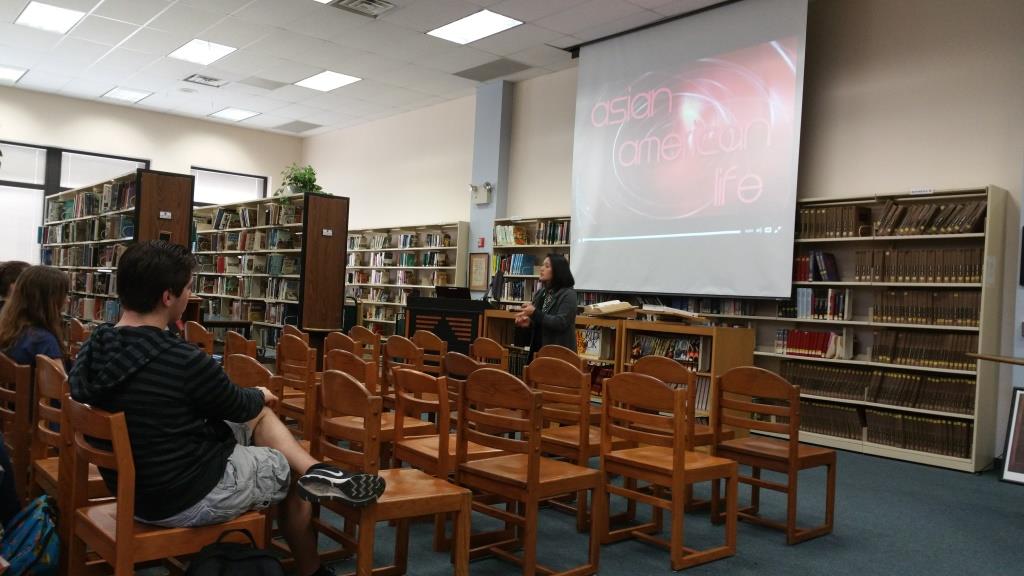

Minnie Roh, CUNY reporter and Glen Rock resident, gave a presentation about Comfort Women to Glen Rock students.

Educating the next generation

“Is she a comfort women?” A student asked his fellow peers pointing to the woman, Minnie Roh, at the podium as the boy walked into the Glen Rock High School media center to listen to her presentation.

Standing in front of the student-audience, Minnie Roh, a petite middle-aged Asian woman with short black hair dressed in mostly dark colors covered by a warm grey sweater, was prepared to deliver her presentation to a group of students who had hardly heard about comfort women.

As soon as the journalism and history students took their seats, Roh began introducing her segment about the sex slaves during World War II who are now elderly women fighting for recognition from the Japanese government, referred to as the Comfort Women.

After showing her CUNY segment, Roh said that, for the women and girls forced into servitude, “it was rape over and over again.”

Roh herself was not a Comfort Woman, she was not alive when the atrocities took place. But she grew up learning about the horrors of these women unlike many Glen Rock students who were not every aware until they watched her segment.

“How can you learn not to make those same mistakes again when you alter the history?” Minnie Roh asked at the beginning of her first of two presentations on Wednesday, March 9. “We don’t learn this very important part of history, even though it is a bad part of history. You have to learn the good and the bad in order to learn from it and build from it.”

History teacher Kathleen Walter teaches about Comfort Women because it “is still relevant in New Jersey because of the Asian population.” One of Walter’s students refused to watch the presentation while others were so interested that they contacted Roh with more of their questions.

“If we can generate a discussion about that and perhaps have people interested in the history and social injustices of the past, it is just education and history that would help form your own opinions and thoughts about past wars and continued the discussion with future generations,” Lord said.

But, Japan is not the only country that tries to change history. For example, Oklahoma is not allowing any state money to fund AP United States History courses because the state excuses the curriculum of focusing on the negative like slavery and not praising the country’s triumph.

“I would like to see them do a little more internal review,” Walter said, referring to the Japanese textbooks. “Whether it is happening in Japan or the United States, it is happening.”

Most Japanese students are not taught about Japan’s wrongdoings, and the textbooks treat the events like a natural disaster, according to AP United States History teacher, Mrs. Kathleen Walter.

“The Japanese say it was just one of those things that was going to happen,” Walter explained. “You cannot avoid a tidal wave or an earthquake.”

Relating to her AP United States History class, Walter explained that it is not unusual for a government to apologize. Starting in 1988, President Ronald Reagan passed a Civil Liberties Act in which the country apologized for Japanese internment and paid each victim $20,000. President George Bush (Sr.) extended the apology by sending a government commission out to research how much money each person lost, so they could try to compensate more than $20,000 each.

Additionally, the Germans have apologized for the Holocaust.

“There are times when the world admits that crimes that taken place,” Walter said. “In this particular case, they acknowledge that a crime has been taking place, but no one wants to hold them accountable because it happened so long ago.”

Three American presidents (Bush, Clinton and Obama) acknowledged the existence of Comfort Women. Because Korea and Japan are both American allies, it is politically difficult to get involved when Japan does not want to recognize the issue.

“Why don’t the Japanese apologize?” Mr. Arlotta, high school principal, asked from the back of the media center.

Roh responded, “We have no idea.” She explained that the Japanese people are concerned about their image from World War II and are trying to ‘whitewash’ their reputation.

“It is just like the Holocaust or what is going on in Syria or anything going on right now. You can’t cover it up because if you cover it up and you just say nothing happened, it might feed other generations for history to repeat itself,” Roh said.

Along with the historical aspects of her segment, Roh also shared logistical journalism problems she had for the interested journalism students who attended her presentation.

“It was a great opportunity for aspiring journalists to hear from someone who has been successful in the field,” said Jason Toncic, adviser to The Glen Echo.

She said that she had trouble finding footage to show while she was speaking in her segment because there are not many photos from this erased part of history.

“I worked so hard to get historical footage that matched,” Roh said.

One person who saw Roh’s work ethic was Sam Shakya, one of the members of the Asian American Life staff.

“We are very compatible in terms of a working relationship. She has a vision and I can really tell what she wants to see,” Shakya, Roh’s editor, said. “I work with the sound, texture and picture, so people can see the turmoil that these women went through.”

With help from her team, she found “fair use” films and photos that are also shown in other Comfort Women features that she could legally use. Walter’s students recognized a photo of a group of a Japanese soldiers lining up in front of a comfort station from a film they watched in class produced by the Chinese government.

“By shedding light of this and saying these type of things happen, it will educate the next generation that this is a human rights violation that shouldn’t of ever happened and we should learn from it,” Roh said.

Giving Asian Americans a voice

Minnie Roh, a Glen Rock resident, is a news correspondent for Asian American Life and was recently nominated for an Emmy Award.

Out of the 318.9 million people that live in the United States, Asian Americans make up 5.6% of the population. Yet until 2013, there were hardly any television shows dedicated towards reporting their lifestyles and needs. The Asian population is similarly rarely showcased on primetime broadcasting stations.

Asian American Life was born out of a necessity to serve the Asian American niche market that was being overlooked. The goal of the show is to share stories, issues and topics that particularly pertain to the Asian American community nationwide.

It is monthly news broadcast that focuses on Asian stories with an American hook, and it runs for 30 minutes. The first show aired on June 10, 2013.

It started as a pilot program and did not take off until 2014. As the show gained popularity, the team expanded and that is when Roh joined. Since the first development, they have added two more reporters.

Roh said that the public is “starved for any kind of reporting” about Asian Americans.

At the time, Roh was not looking for a job with a huge time commitment since she has children and, thus, a more restrained schedule. She was no longer interesting in standing in the middle of a storm and breaking the news. Her friend casually mentioned that the show was hiring, so Roh sent in her reel, went for an interview and booked the job.

The Asian American Life team currently consists of five reports and an anchor, all who have backgrounds in local news. Some have been journalists for over 20 years.

Senior producer of Asian American Life, Maria Lord, used to be a producer for NBC News for the TODAY show.

“We have a small team, but we all came from a network,” Lord said. “We share stories in a news magazine format, so any subject or issue that we cover, we present it in a way that you would be on mainstream network news.”

The show broadcasts on the CUNY channel, which also airs shows about different ethnic groups including African Americans and Hispanics. The shows consist of in-depth reporting on each specific subject.

Roh enjoys being able to focus on one community and being able to meet their needs as a journalist.

“What we try to do is raise some of these issues, so they will not be forgotten because they are an important part of history. How does it relate to people here in America? Why would they be interested?” Lord explained.

Most of the show’s reports are not investigative, but rather light and feature-like.

“Comfort women is probably the most hard-hitting news that we have ever done,” Roh explained. “I am currently working on a story about exploited workers and undocumented workers. That is hard hitting as well.”

On traditional news broadcast shows, the reporter has to share the news in a way to reach the entire viewing audience. It is also a struggle for reporters to be in-depth with their stories because they do not have the resources and airtime. Asian American Life does not have these same restrictions.

“This is a great show now because I can really sink my teeth into Comfort Women, which really I would have to fight to get on the air somewhere else,” Roh said.

Asian American Life is a nonprofit show, so it is hindered by budgetary constraints and other issues.

The show is also New York based, so they do not broadcast national stories.

The team uses Skype and other technological applications for interviews and research to limit travel.

The team runs their weekly meetings like a regular newsroom where they brainstorm and pitch ideas. Each journalist comes to the meetings prepared with a good argument for when they have to pitch and defend their stories.

“We try to tell stories that are unheard of or untold that you might not necessarily see in network news,” Lord said. “We try to keep it topical and related to newsworthy events that are happening right now.”

According to a Nielsen report, Asian Americans are the leaders in social media usage. To address its audience, Asian American Life uses Facebook and Instagram. Its Facebook page has 2,254 likes and it has 20 followers on Instagram.

“We have had great success because we are finding out that people are following us from Australia and Philippines. To our surprise, even South America,” Lord said. “Even though people might not see our show here in the United States, because we exist online, we are reaching all over the world.”

Minnie Roh’s Comfort Women segment has reached viewers worldwide through the internet.

“I think that in that way, even if the Japanese government is not willing to step up, through the power of social media, not people will know and it is another way of educating the world,” Roh said.

Minnie Roh speaking in her Comfort Women segment for Asian American Life.

Behind the scenes

“College is a time to explore. Do whatever you want. Do not think about your future. Just study what you want to study.”

Those were the words Minnie Roh’s father said to her when she decided to major in linguistics and anthropology as an undergraduate at Columbia University.

At the beginning of Minnie Roh’s career path, she had no idea she wanted to be a reporter. Her first job was as a page at NBC, and she gave tours, had daily assignments and worked in various departments to see what she was interested in.

Roh worked in sports and programming before she found her passion for the news and decided to attend Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism.

“I had no pressure, but in a way, it kind of set me back from the rest of my peers because everyone who wanted to do journalism was already on that path,” Roh said. “I am always consistently a couple of years later behind all of my peers. But it doesn’t matter. At the end of the day, we are all kind of equal now.”

Once she graduated from Columbia, she returned to NBC and answered phone calls for their Nightly News desk.

“This time it was a little more like we could go out and do quick interviews for producers and we thought we were so great being able to do that,” Roh explained. “That kind of built the foundation and I decided I wanted to go on.”

Roh was then hired by NBC’s Dateline as a producer, where she created 10 to 15 minute packages.

“When I was on it, we did a lot more investigative stories and really good hard hitting news stories,” Roh said. “Now it is all of these one hour crime interpretations.”

After about seven years at Dateline, Roh felt like she was missing something, so she left and decided to go on air at age 33. She shot, edited, wrote and took live shots for the Time Warner station in Raleigh, North Carolina.

She quickly realized that she hated shooting and needed a photographer.

“So then I went to Richmond in Virginia and that is when I really cut my teeth on local news,” Roh said. “I worked there for about 7 years and I anchored and I reported and I did special consumer reporting too. That is where I really got my reporting jobs.”

Soon after, Roh had children, moved up to New Jersey and slowed down her career, only freelance reporting here and there. She taught reporters at a Korean news station how to report, edit and write articles. Then, in April 2014, she was hired as a reporter at CUNY for Asian American Life.

“Minnie is a very focused, smart, intelligent journalist,” Maria Lord, senior producer of Asian American Life said. “It is wonderful to work with her. She has strong story ideas that are always investigative by nature because she came from an investigative newsroom background.”

“She is very inspiring because her vision to try to tell a story is amazing,” Sam Shakya, her current editor, said. “She is very thorough and thoughtful and if I need something, she will get it for me.”

Although Roh did not win the Emmy-award for which she was nominated, she still felt proud to have brought so much attention

*Screenshot images compiled from Minnie Roh’s ‘Comfort Women’ segment.