Glen Rock: A Retrospective

April 28, 2016

A meeting on Main Street

The air was thick and hot and the sun was just about to retire for the day. The clear sky was filled with fireworks, almost as if it were the fourth of July.

Besides the pyrotechnics, the only other source of light was cast from five Roman candles held by five men dressed in white robes from head to toe, including white hoods.

These men stood patiently next to another man dressed in all green, who was clearly their leader. They waited in the middle of the Marinus Estate lawn, right by Main Street, as eager townspeople filled in the field.

the right are acres of land where the KKK meeting

took place.

The half-dozen men waited until they were overwhelmed by the anxiousness of some 300 curiosity seekers to begin the ceremony. A sign reading, “Ridgewood Unit No.72, K.K.K.” was positioned right above the platform on which now only the man in green and an American flag stood on.

One of the klansmen asserted himself in front of the crowd; he introduced a “local minister” as The Chairman of the evening. This man, however, was not a local member. He came from New York City to take part in the event.

The Chairman began the meeting by leading a prayer many did not know. Then he spent a great deal of time addressing The Klan and matters that only pertained to them. Many goers questioned their reasonings for attending such an event.

Following The Chairman, the man in green was introduced as the main speaker of the evening. He was presented as “Dr. Finger of Jersey City.”

Dr. Finger spoke contradictorily about the K.K.K, saying that they do not believe in mobbing nor do they condone death or any violence.

Finger said, “We believe, in one hundred percent Americanism, and that is all there is to it.”

Finger emphasized highly on the fact that radicals should not be allowed in this country. He also mentioned Sacco and Vanzetti, two Italians who were executed for murdering a paymaster for a shoe company and his guard.

“They should have been deported long ago,” Finger said regarding the execution.

He then narrowed in on more local matters, speaking about how a janitor at a Glen Rock school had been discovered running a whiskey still in the school’s basement. Although normally reprehensible, this act was magnified by the regulations of the Prohibition Era, which banned the production, sale, and importation of alcohol from 1920 to 1933.

“You should get after your officials and together you should run this man out of town,” Finger said, again touching on the ideas of “one hundred percent Americanism.”

Finger took sarcastic approaches to relay the thoughts of The Klan. The crowd seemed to be amused, and laughed at most of the topics and ideas that the speaker touched on. However, the laughter did not linger for long after the speech.

When the speeches were concluded, the “burning of the cross” ceremony begun. The KKK cross burning is referred to as a “cross lighting” ceremony, differing it from the illegal protests against the honoring of Christ.

Four of the hooden members in white stood around the cross and waited there until the flames dwindled away into the darkness.

The memories of Nancy Mapes

The Christmas trees were burning in the vacant lot next to 561 Doremus Avenue.

They were tossed into a disheveled heap, the needles and branches still bent from overweight Christmas ornaments. Strands of tinsel glinted spookily in the dark.

A fire engine was parked and a crowd of onlookers gathered while Nancy Mapes’ father, B. Walton Romefelt stood over his conflagration.

The flames, however, did not linger for long. That December afternoon in 1940 would be the last time the Romefelts held the tree burning festivities.

Dec. 7, 1941. President Franklin Roosevelt called that day, “a date which will live in infamy.”

On that day, Japanese aircrafts attacked the US Naval Base in Pearl Harbor of Hawaii. The attack killed 2,400 people; the American battleship U.S.S. Arizona was completely destroyed.

On Dec. 6, 1941, the U.S.S was filled completely with fuel; a total of 1.5 million gallons of gasoline. The abundance of petrol needed for the war required the states to ration gasoline and home heating oil.

For the Romefelts, this meant that the car was only used for emergencies, the thermostat was maxed out at 60 degrees, and the fireplace burned coal.

Being that the car was only kept incase of an emergency, Nancy, her two sisters and brother had to walk everywhere.

The night before school, they would hang their school clothing on the fireplace screen ensuring a warm wardrobe for the next morning. This routine was crucial in the winter, for even if it rained, snowed or was below-freezing, the Romefelt kids would be found walking to school.

They would awake early enough to make the walk down to 670 Doremus Avenue, up to the corner of Maple Avenue and Rock Road just in time to catch the bus going to Ridgewood High School.

Seniors at Ridgewood High School were able to work at the Allendale Celery Farm, weeding the vegetables as an alternative to taking exams due to the lack of farm laborers. Those who worked on the farms were allotted extra gasoline. Nancy worked in the farm and earned gasoline for their family car.

Despite the war and the issues surrounding it, Nancy’s education was never hindered. Like any high school student, Nancy had to invest hours into studying and completing assignments.

However, in the 1930’s and 1940’s, homework wasn’t assigned until a student entered the ninth grade. The idea of waiting until junior high school to complete work at home was influenced by John Dewey, an educator, American psychologist, philosopher, political activist and social critic.

Dewey cultivated the system of educating the “whole child.” This system deemed it necessary for schools to offer art, music, world language, physical education and nutritious lunch options.

In elementary school, children were taught songs, and games. There was a huge sandbox in that classroom at Byrd School where students were encouraged to show off their creativity.

At Ridgewood High School, when students had a strong educational background, they were taught to read music.

The Romefelt family believed education was extremely important. When it came to Nancy’s school they often said, “When you educate a man, you educate a man. When you educate a woman, you educate a family”.

The big stone from the sky

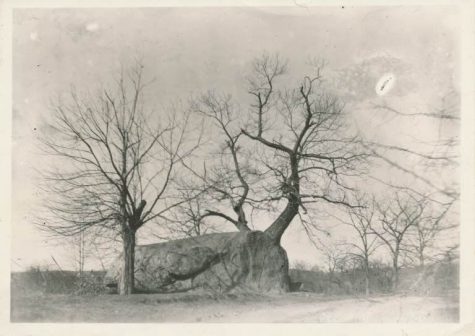

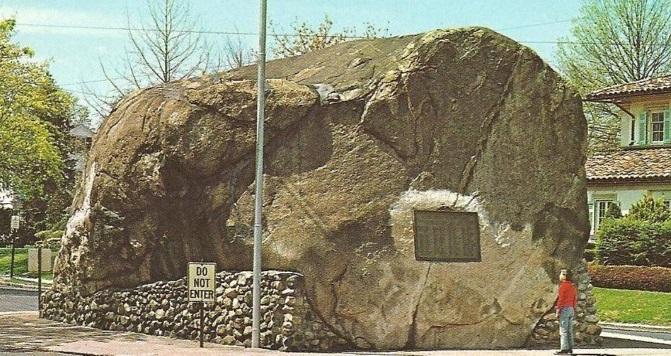

The conspicuous 570 ton boulder left at the end of the Ice Age by a Hudson Valley glacier acted as a trail indicator for travelers making their way to the City of Paterson.

“The Lenapes used it as a marker along an important trail and named it “pamackapuka”, meaning ‘big stone from the sky,’” said Susan Tryforos, Glen Rock Historical and Preservational Society president.

The Native Americans were the first colonists of the borough of Glen Rock. They used the heavily wooded area, now Doremus Avenue, to hunt. The stream close to the woods, was used for fishing.

The Rock was the center of their inhabitation. It was in line with the trail coming from Hackensack Arcola, which they used to travel up to Oakland. It was there that they would catch larger fish in the Ramapo River.

When they needed to pass along information, the Lenape would hold council meetings on The Rock. They would send smoke signals to surrounding tribe-members, often times the fire was lit atop The Rock.

In the 1700s, Dutchmen purchased land deeds from the Lenni Lenape. Once the Dutch settled into their New Jersey routine, they cleared the area of trees while creating efficient farms. The roads were created around The Rock, now known for foraging by the Continental Army and The British. The landmark was even noted on the Revolutionary War map.

On Sept. 14, 1894, the borough of Glen Rock had officially separated from its former townships of Ridgewood and Saddle River. A meeting was held to discuss the matters of choosing a name for the new town.

Most of the councilmen had agreed on originally calling the new town, South Ridgewood. However, they decided against that, figuring people would become confused with the bordering town of Ridgewood.

Charles M. Veil, a resident of the borough is credited for proposing the title, Glen Rock, in literal meaning, Rock in a narrow valley.

Though there was always a growing popularity of the 36 foot long boulder, for hundreds of years, The Rock was actually partially buried.

In 1912, the south side of Doremus Avenue, now the location of Byrd School, was being developed. Smith-Singer, one of the builders working on this project, wanted to get rid of The Rock completely.

“You can go ahead and blast The Rock as long as you do not disturb any of that 18 inches,” Bunce told the construction team.

Admitting defeat, Smith-Singer built the new section of Doremus around The Rock, unearthing the surroundings. When the rock was excavated, it was a whole ten feet taller making it a total of 22 feet high. Builders turned The Rock over to the town as a borough park.

After the first World War in 1921, there was a metal plaque attached to The Rock, facing Rock Road. The plaque lists the names of fallen soldiers from the area and remains a memorial for those who passed away fighting in WWI. To this day, every Memorial Day and Fourth of July a wreath is placed on the plaque, honoring the soldiers.

It was not until 1964 that The Rock was deemed a historical site, and in 2012 the landmark was featured in an issue of The National Geographic magazine. Another role The Rock holds is that it marks the burial of a time capsule that is to be open in the year of 2044, on the borough’s 150th anniversary.

Until then, The Rock serves as a sense of identity for the town. The history surrounding it is what makes residents so proud to show visitors, proud of the town in whole.

The life of William Mitchell

The streets of Brooklyn were so crowded with people that there was no room for anyone to move, at all. There were couples, families, friends, even strangers embracing one another. Confetti flew from the air as cars unloaded smiling men in uniform. World War II was over.

Following the war, their was an abundance of joy and freedom cracking through the faces of once solemn and terrified Americans. When soldiers arrived home they looked for peacetime jobs. The production of weaponry and other war equipment was stopped. The American economy was stronger than ever.

Millions of people moved out of the suburbs and into small town areas. The population in Glen Rock grew by more than 2,000 from 1940 to 1950.

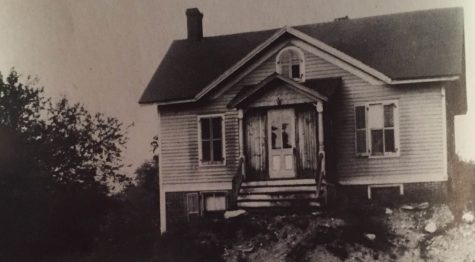

With the growing population came the construction of 1,500 houses. One of those houses being the birthplace of resident William Mitchell.

William Mitchell was born on Aug. 27, 1950 in a three-story home in a time when the closest hospital was just about nine miles away.

In agrarian societies, most babies were born in homes due to the fact that hospitals were far away. After the war, Glen Rock had started the transition from an agrarian area to a very suburban family-oriented town. But, in 1950 there were not local hospitals like there are today.

The Mitchells had planned on delivering their baby at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson. Despite the planning and preparation, at 2:30 am on that hot Saturday, they were caught off guard and did not have the time to make the trip.

Mitchell’s mother always had very short and compressed labor times, so everything happened very quickly. With a doctor on the way, it was decided that Mitchell would be born at home.

Earlier that day, with the anticipation of knowing that their second-born was on the way, the Mitchells painted the new crib a fresh coat of white.

Due to the premature birth of their son, the crib was not given enough time to dry. It was setting in the basement and was still tacky with paint.

The Mitchells turned to one another, each hoping that the other had an idea of where to lay their baby to sleep.

The best solution was for them to put him in his sister’s play doll carriage. Weighing only a few pounds, he fit perfectly in the carriage.

The next morning, Mitchell’s sister awoke and groggily walked downstairs. Her eyes widened when she found what she thought was a new doll in her carriage. Within seconds she realized that it was alive and that it was her newborn brother, William Mitchell.

Due to the fact that the great majority of children were born in hospitals, Glen Rock birth certificates were rare. It was not so easy for Mitchell to receive his.

Mitchell’s birth was such a rush and nobody was prepared; the town did not have birth certificates readily available. Normally, a child would be granted a birth certificate minutes after entering the world. Mitchell received his several days later.

Someone had to climb into the attic of the Municipal Building and search for the stack of blank certificates. Finally, around a week later Mitchell was given his Glen Rock birth certificate.

The day he was born, Mitchell’s roots were planted in Glen Rock turf and they have been enriched through the past 65 years of his life here.

In 1978, Mitchell moved here with his wife Karen; they have lived in the same house since where they raised their three sons.

Mitchell had the opportunity of watching as his children graduate from Glen Rock High School, on the same stage as he did. He was a part of the tenth graduating class.

Now, with two grandchildren a part of the Glen Rock school system, Mitchell hopes to be able to someday see them too graduate from GRHS.

The five generations of Mitchells that have lived in the town of Glen Rock have passed on the importance of growing up in such a family-oriented neighborhood.

“Even now, amongst my sons I think there is the same sense that this is special and a great place to grow up,” said Mitchell. “I’m very pleased with that and I always felt that when I raised my family here that would be part of it.”

Then and now

Thanks to The Glen Rock Historical and Preservation Society for their photographs.

Susan Spar • May 4, 2016 at 11:35 pm

After that chilling tale of the kkk (which was news to me), I thoroughly enjoyed the tales of our Rock in the Glen, and the families, native and subsequent, who created such a lovely town.

Ross McDonald • May 4, 2016 at 1:59 pm

Class of 1969.

Gloria Smith • May 4, 2016 at 9:07 am

Wow Julia! What a great article! Makes me very nostalgic for this sweet little town I was lucky enough to grow up in. And I’m thrilled for that sweet little girl who was my neighbor in Charlotte, who along with her family will have the same wonderful memories of growing up in such a wonderful place!!

Julia Rooney • May 4, 2016 at 3:56 pm

Hi Gloria! Thank you so much for reading my article and for your kind comments! My mom says please come back and visit. : )

Laura Hopper Quinlan • Apr 29, 2016 at 8:12 pm

We were neighbors of the Mitchell’s and William Mitchells’ sister, Carole, was an early playmate of mine. My mother, “Peg” Hopper was present at Bill’s birth. Not sure she was much help, but I guess they sought out any help they could get. Bill called my mother Auntie Peg for years and they had a standing “luch date” once a week while Bill was in grade school.

Glen Rock was and is a great place to grow up.

Carole Way • Apr 28, 2016 at 11:10 pm

Wonderful job, Bill. Loved reading it! I had forgotten the part sbout my thinking I got a brand new doll.