A river runs between us: The opportunity gap separating Glen Rock from Paterson

December 3, 2015

Awakened by the soft touch of his mother’s warm hands against his back and the crisp breeze of the open window beside him, Griffin N. groggily flung his rested legs from beneath the warm cocoon of his Pottery Barn quilt and sleepily trudged downstairs.

Greeted by the welcoming glow of his television against the dark of the morning and the familiar hum of his laptop, he eagerly signed onto the MacBook and almost immediately became mesmerized.

This trance was routine for the ten-year-old and was only shortly broken by the rallying calls of his mother, which gradually grew more aggravated as Griffin failed to eat from his bowl of cereal awaiting him.

He absentmindedly listened as his mother droned on about his after school plans to attend art class followed by his friend’s birthday party at a trampoline house. She then shuffled to arrange his backpack, heavy with school supplies.

Griffin stared into the colorful bowl, toying with the milk and leaving most of the vibrantly colored loops untouched.

Five miles away, Carlos J. looked up from his bowl of Froot Loops and his glance was met by the dreary morning sun dripping through the closed windows of his apartment. He slurped the remaining milk in his bowl and grabbed his empty worn backpack resting on the couch.

The emptiness of the small apartment was punctuated by the muffled echoes of shouts and sirens from the streets below.

The nine-year-old fumbled to unlock the series of deadbolt locks on the door as a slight breeze traveled down his neck from the ceiling fan above.

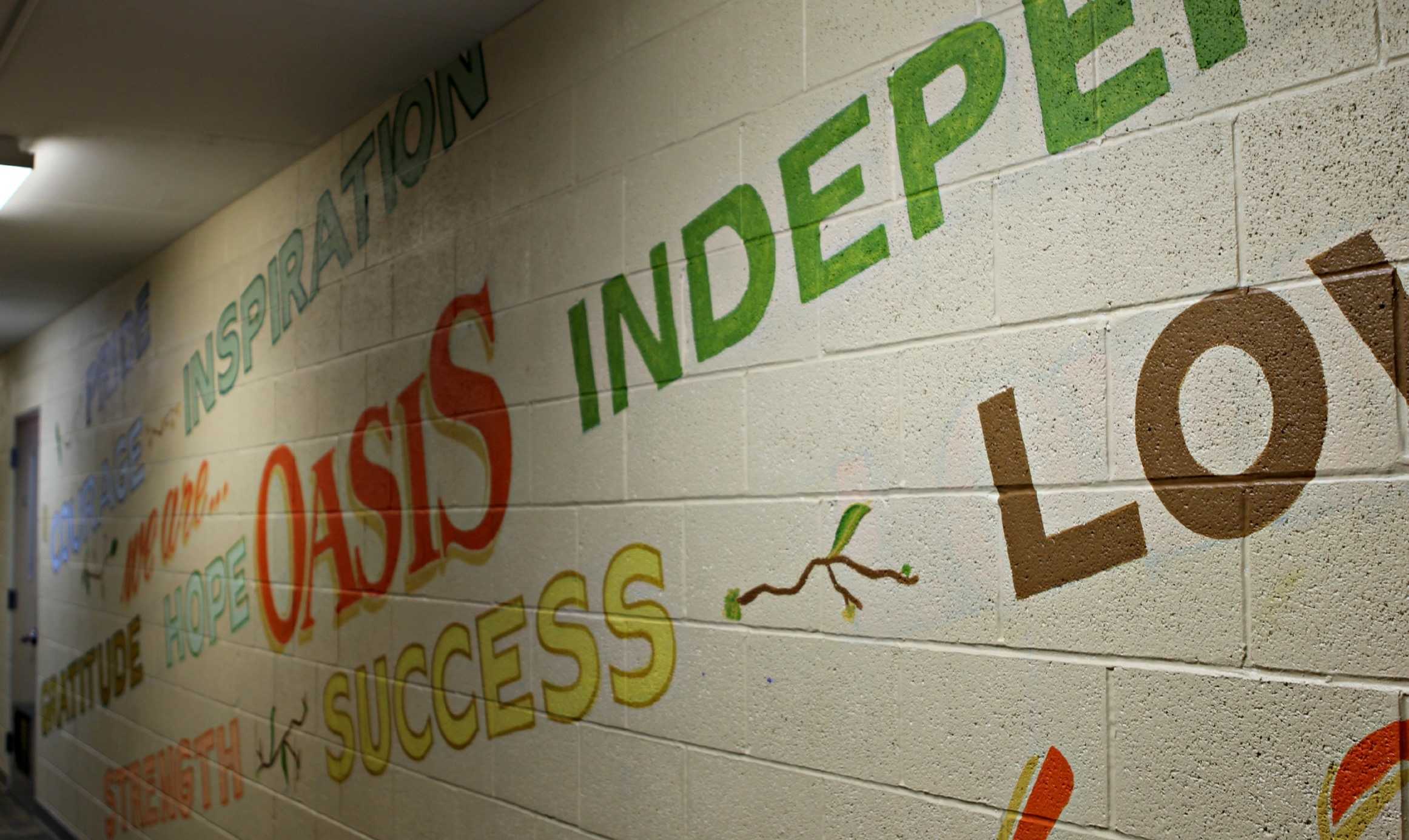

Oasis serves as a beacon of hope among the impoverished Paterson neighborhoods.

With the triumphant click of the last lock Carlos’s eye caught the inviting warmth of a yellow post-it left by his mother before leaving for work. The words “Oasis after school” were hastily scribbled on the square of paper.

With a now contented look, Carlos slammed the heavy door and slipped out onto the foreboding concrete streets.

—

Griffin lived in Glen Rock, a suburb of New Jersey known for its affluence.

Across the Passaic River in Paterson lived Carlos, a boy nearly the same age but with a much different upbringing.

Escaping poverty in the Oasis

Nestled in the depths of Paterson, Oasis is a haven for women and children who are overcome by the adverse cycle of poverty. Oasis aims to revolutionize the lives of women and children who enter into their doors by breaking this cycle of poverty through programs intended to clothe, inform, feed and inspire women and children in need.

“Right now we’re working really hard on creating collaborative relationships in the community with local organizations and agencies that are serving the same population as we’re serving,” Jennifer Brady said, Executive Director of Oasis and a member of the Oasis board since 2004. “A big part of what we need to be doing is getting out and raising the money. We are operating on a budget deficit. We are bursting at the seams in terms of space. We could double every program tomorrow if we raised the money.”

Executive Director Jennifer Brady stands in front of Oasis’ nest inscribed with generous benefactors.

Oasis caters to women and children living in the underprivileged city of Paterson. They offer adult education courses, youth development programs, basic needs and social services to individuals that need a helping hand.

“To see a woman crumble in front of you and want to give up… this is every woman’s story. She’s just having her moment, but we all have our moments. And she’s got nowhere else to go but here. We’re her only hope,” Brady said. “For a lot of these women and children, Oasis is making such a huge difference in their lives. Without us, we don’t know what would happen to them.”

Although Oasis extends its hospitality to everyone, it remains difficult for many women to accept aid. For women who fall victim to domestic violence or alcohol and drug abuse, every day is a challenge. These distresses make braving the world and getting out of bed a challenge in itself.

“It’s hard. Getting help is a change of lifestyle and there’s a fear of the unknown. You know what it is on alcohol and drugs. You know what it is on domestic violence. The women don’t just pack up and leave because they’re getting abused,” Jim Walsh said, Chief Operating Officer and Director of Youth Development Programs. “If you wake up to someone telling you every morning ‘you’re no good, you’re no good’ you’re going to think you’re no good. That’s why it takes courage to come here.”

The women of Oasis are a rare sight to see. Not because they’re off limits to journalists but because they spend the short hours of the day working from dawn until dusk, reserving the meager hours of daylight left for time with the children whom they work so hard for.

Although the stories of the women at Oasis are unique from one another, they all share a common source of hope: their children. The innocence of the children who attend Oasis radiates hope and optimism for a better future, regardless of their situation.

“Once you come down here and see the women and the children, you just fall in love and you keep coming back,” Brady said.

Walsh and Brady’s Bunch

Everyday, shortly after the dismissing bells of schools across Paterson chime, 85 children ages six to twelve gust through the heavy doors of Oasis into the cafeteria, the heart of Oasis.

“I open up the gates and open up the door and, anything after that, I don’t know what’s going to happen. That’s the truth,” Walsh said. “The hours that I have in the morning are when I can catch up on some work, but once the doors open you really don’t know what’s going to happen.”

The Michael Wagner After-School Program is a three-pronged program: nutrition, education, and socialization. The nutrition segment works with the community food bank and provides the children with a hot meal immediately after school. For many kids, the meal provided by Oasis is their only food for the whole day. The education sector of the program employs both professional tutors and volunteers that assist children with their homework.

Arguably the most essential part of the program, however, is the social benefits that the children at Oasis receive. The children develop relationships with others in a stable environment, which is imperative to their success in the future.

“When we go on trips people will tell me how great our children act and it honestly freaks me out. I look at them and go ‘really?’” Walsh said. “Each one is unique, you know each one has a different story.

Not only do the children acquire skills that allow them to healthily interact with one another, they also learn how to respect authority and establish familial connections with the volunteers and staff at Oasis, something that is not necessarily guaranteed at home.

“Although we offer them [the children at Oasis| tutoring and workshops, honestly the most important part is the people that care about them, people that are invested in their future,” Brady said.

A rare success story

On a brisk Friday in November, as a winter chill swept the streets of Paterson, Jennifer Lindo’s life changed forever.

Lindo, a high school student at the time, strolled through the doors of Oasis, stopping only to stamp her time card as she slid her backpack off her weary shoulders. Succumbing to habit, she trudged two flights up the gray concrete stairs of Oasis. She walked briskly through the third floor hallway, passing the mural of inspirational words painted on the pale yellow wall.

“Jennifer!” a man bellowed down the hallway. Awoken from the daze of her routine, Lindo stopped.

Although Lindo didn’t know it at the time, this man would revolutionize her life nearly as quickly as it took her to punch in her time card.

The man’s name was Walter Ginsberg.

Ginsberg volunteers at Oasis and contributes to the organization’s GED program and aids in computer classes taught on Friday mornings. His warm face blends into the unique amalgam that is the Oasis family.

Ginsberg and Lindo had never been close, but it only took him eight words to begin a lifelong connection: “So, I heard you wanna go to college?”

Lindo was floored.

“I wasn’t planning on going to college. I was planning on going into the military. I mean everything had changed that one day,” Lindo said. “I told him yeah, but then again I was like ‘I rather not. I rather just go into the military.’ So ever since that day everything changed. I changed my mind; I was like ‘You know, I’m here in this country for a good living, to go to school.’”

Lindo was born in the United States, but both of her parents are Peruvian.

“I do see the struggle that my family has to deal with over there in Peru,” Lindo said. “My mom always has told me that I should be glad and blessed that I’m here and that we’re able to have financial aid and things like that.”

Ginsberg approached Lindo at the right time, just as the chaos in her life was beginning to subdue.

Lindo had just transferred from John F. Kennedy High School, known in part for its students’ struggles. Students at JFK High School would continuously cut class and roam the halls in gangs, only to select an innocent student to beat right there in a classroom.

“It was hard for me. I just wanted to give up. I thought, ‘You know what, I don’t think school is for me,’” Lindo said. “But I had my mom and brother’s support and I had Jim’s support and I had a lot of support from Oasis.”

Lindo transferred to Silk City Academy, a small school in Paterson. Before transferring, she had struggled to keep up and found herself regularly in trouble and skipping classes.

“When Jim had seen my freshman year grades he was very upset and he said ‘In order for you to work here you have to bring up those grades,’ so ever since that I changed my grades,” Lindo said. “I was literally an F student and now I’m in Honor Society. I’m now one of the top people in my class with the highest GPA.”

Although she found herself improving drastically at her new school, the transition wasn’t easy. The summer going into her senior year, Lindo wanted to return to JFK High School.

Lindo never expected such a vociferous response to her desire to return to JFK High School. Her school principal and teachers at Silk City Academy exhorted to remain at the school.

“I never heard a principal tell one of their students, ‘Why are you leaving a school where you came from nothing to become an excellent student?’” Lindo said. “My teachers would say, ‘You’re not going to be in Honor Society at the school you came from. Why would you go back to a school you did horrible at?’”

Lindo realized that if she returned to JFK she would end up failing out of school. Without a GED she wouldn’t be able to hold a job or even enroll in the military, so she made the decision to continue her senior year at Silk City Academy.

“Now I actually love it [Silk City Academy], I love that school. That and Oasis changed me,” Lindo said. “The way I am now is way different than who I was before.”

Walter would hound Lindo for her GPA and report card. He would continuously remind her that she would go to college.

“The biggest fight we had in getting Jennifer to college was nobody would call us back to release her transcript because they don’t do that there — they don’t do that in Paterson — they don’t have kids going to college,” Brady said.

For the first time in Jennifer Lindo’s life, though, she felt as though everyone was rooting for her.

“I felt the love. I fell in love with the fact I had wonderful people around here who pushed me,” Lindo said.

For eighteen years, Lindo had been doubted and denigrated. She was surrounded by people who told her she couldn’t.

“I was told I wasn’t enough. I wasn’t going to be anyone in life,” Lindo said. “I’m not going to lie. It was hard because when you have people doubting you it’s like you’re not worth anything; that’s how I see it.”

Principals and teachers disregarded Lindo because of her behavior and poor grades.

Even her father was guilty of overlooking her. He would regularly compare Lindo to her older brother. Lindo’s brother attended Passaic County Technical Institute in Wayne, an establishment regarded for its rigorous caliber of education.

“I will always feel like the one who wasn’t worth it. College made me look forward to proving my father that my brother is not the only smart one between us,” Lindo said.

As Jennifer began filling out applications, she realized that she wouldn’t have gotten this far without those doubts- those doubters. She became conscious of how far she had progressed and for the first time in her life she experienced a foreign feeling of pride.

A feeling made possible, in part, by Oasis.

“Honestly, in a way, I thank those people that told me I wasn’t going to be anyone in life because that’s what made me strong,” Lindo said. “I actually thank them for telling me that [I wasn’t good enough] because that’s what made me stronger and had made me someone.”

On a snowy day in late February, Jennifer Lindo was awarded for her vigor.

Removing two thick envelopes from the hatch of her mailbox, Lindo ignored the sting of the cold against her skin and rushed inside.

She had done it.

Jennifer Lindo was accepted to Mitchell College with a $10,000 scholarship, Mercyhurst College with a $60,000 scholarship, and the College of Saint Elizabeth with a full ride.

Her love of children and experience as a counselor at Oasis has inspired her to study to become a special education teacher in the future.

“I like kids, that’s why I work with kids. When you’re with them you just forget about your problems and you focus on them,” Lindo said.

Lindo believes that her tribulations growing up only have strengthened her qualifications as an educator.

“I’ll always talk to the kids because I know how it feels when people tell you, ‘you’re not going to do anything in life. You’re not going to be anything’,” Lindo said. “I know how it feels when people tell you negative things. So I try to be the bigger person and give them the positive, because that’s what I have to do. I can’t tell them ‘yeah you’re not going to be anything’. No, that’s not how we are.”

She hopes to use her life story as an example for children who aren’t afforded opportunities.

“I would love for them [the children] to hear my life story and what I went through to be who I am,” Lindo said.

As a special education teacher, Lindo will act as a mentor to children just as Oasis was to her.

“Life is not easy at all. You have to go through so much in order to be successful and I’m actually proud of having Oasis around me,” Lindo said. “I’m very proud of myself. I’m very proud of who I became.”

Oasis has remained a permanent part of Lindo’s life for the past eighteen years, and the compassion of those who work there has allowed her to rise above the negativity in her life.

Lindo’s departure from Oasis has only now become a reality.

“It’s going to be hard because I will have no one on top of me. I’ve had them since I was a baby and they’ve seen me grow and now they’re seeing me move on to a new chapter in my life — a new beginning,” Lindo said. “Everything they have told me, the words, the speeches, I will just have to keep it in my heart. I might have to write it in a notebook so I could go back and see everything they told me. Because I’m not going to have them by me, I’m just going to have their words.”

And as for Walter Ginsberg, he will always stand as a representation of hope and the bearer of a new future to Lindo.

“He’s basically my advisor, but I see him as an uncle,” Lindo said. “I will make him happy. I will make him happy by graduating college in Honor Roll and I will get my degree and my Masters as a thank you. I’m not going to let him down.”

Lindo will be attending the College of Saint Elizabeth this fall.

The unfortunate reality

Yet in Paterson, Jennifer Lindo’s story is an anomaly.

“College is not part of their conversation. It’s not part of their thinking. It’s the opposite almost, it’s not cool for you to want to succeed here,” Jennifer Brady said. “Going to college is not presented to them.”

For many Glen Rock High School students, it is routine for college to be discussed at the dinner table.

“It’s normal for the word ‘college’ to come up at least five times during the day. It is nearly impossible to avoid the topic both in and outside of school,” said Emily Rabens, a senior at Glen Rock.

However, just a town away in Paterson, a discussion of an academic future is incredibly unlikely.

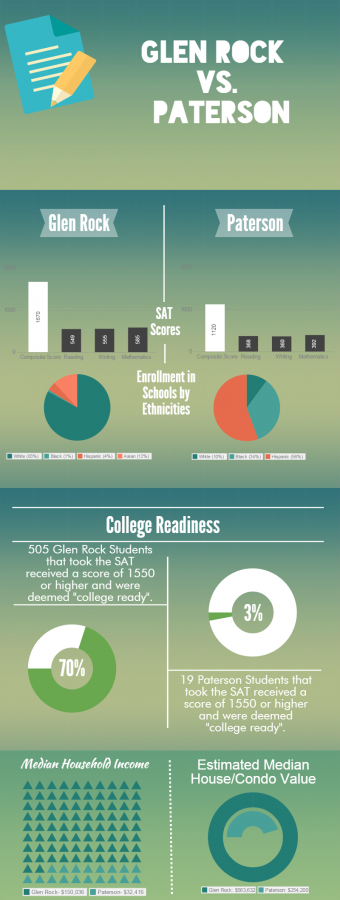

“These kids have the same dreams as the kids in Glen Rock. They want to be doctors and lawyers and engineers and build buildings, but they don’t have the opportunity here,” Walsh said. “If you went into the Public School system and saw how decrypted and dysfunctional it is… when the kids in Paterson take the SATs, 3% of them are deemed ‘college ready’. 3% based on their scores.

And then they have a fear of testing. Big fear… because of failure. You know when you hear ‘Oh, you failed the test,’ well not really. You took a test and you didn’t get enough points. It’s a completely different world. The system is working against them. They have to really be self-starters and self-motivated or have Oasis to get out.”

According to College Board, approximately 43 percent of students who take the SATs attain the college ready mark. To be deemed “college ready,” students must receive a combined score of 1,550 on the test. In 2013, the average score for students in Paterson was 1,120.

The company who administers the test, College Board, states that students who have reached a score of 1,550 and have therefore been deemed “college ready” have a 65-percent chance of getting a B- or higher in their first year of college. The company also says that 54 percent of the students who receive a score higher than 1,550 are likely to get a bachelor’s degree within four years of college.

For Brady, she straddles the enormity of two very different worlds.

“My kids go to Northern Highlands, they have a full engineering program. You could take engineering for four years. That doesn’t exist for this population, so they’re not getting that. So when they get to the SAT or the ACT and half of it is math, there’s no way that they could do it,” Brady said. “They’re also not being exposed to those career opportunities. If you never experience it, it’s not going to happen.”

Oasis offers tutoring and educational workshops to compensate for the absence of instruction at school. The faculty of Oasis and IBM are currently working to introduce STEM to the organization, a science, technology, engineering, and math course that would enforce subject areas that Paterson children are experiencing difficulty with. The project, however, will not be launched until the non-profit receives the funding to effectively execute the program.

Despite forward-looking programs like STEM, the aspirations of Paterson students are often restricted due to finances.

“Two days ago, I was sitting up here just like this and a little ten year old girl came into my office. Her name is Claudia, and she was just helping me clean up a little bit and I said ‘Claudia, what do you want to be when you grow up?’ and she said, ‘I want to be a doctor, but I don’t know if my mom is gonna let me go to college,’” Brady said. “These stories are why we do what we do, but to experience it every day is just amazing.”

The lack of opportunity in Paterson encourages the cycle of poverty that the city is struggling with. As a child in Paterson, experiences are restricted to the 8.7 square miles of paucity.

“If you don’t experience it, you don’t dream it,” Walsh explained.

Life across the river

The destitution of Paterson is juxtaposed by the surrounding abundance of Bergen County. Neighboring towns like Glen Rock, Ridgewood, Hawthorne, Fair Lawn, and Saddle Brook celebrate upper middle class lifestyles and white-collar careers.

The youth, accustomed to wealth within these towns, are only fleetingly familiar with their less fortunate neighbors.

“I think it’s hard for kids in our communities in North Bergen County to really understand, not just about being poor, but about the lack of opportunity,” Brady said. “These kids don’t have grass, they can’t go to a park in Paterson, they’ve never played in the sand, they don’t have a lake to go to, and they don’t have a pool to swim in. So their experience is so vastly different five miles away from where you and I live. You know it’s hard to grasp until you get here and get to know the kids that are here.”

The circulation of local news between Paterson and its neighboring towns is also nearly nonexistent, despite the proximity of the communities.

“One of the boys who is a tutor in our after school program, his father was shot and killed two weeks ago. This happens in Paterson, it doesn’t happen in Glen Rock. You didn’t even read about it in the paper because it’s not news here,” Brady said. “People take for granted their lack of fear. You don’t have to be afraid. You may be afraid, but you don’t have to be afraid. These kids really have to be afraid.”

The dissimilarities between the communities may appear evident, yet there are many things that individuals take for granted that may continue to astonish even the masses.

“People take life for granted. No really, life. Having the freedom just to be able to go out. One of our girls that we hired through a grant goes to St. Louis College. She just completed her first year and she was saying to me yesterday that she was having a hard time in the beginning adjusting. And I said, ‘Why?’” Walsh explained. “She said, ‘Because of the trees, the grass, and no sirens and gunshots.’”

Robert Resnick • Dec 4, 2015 at 1:16 pm

As a GRHS grad who is married to a JFK grad, I deeply appreciate the work you have done in telling this story. The gaps are serious and need to be called out more often. This is an excellent piece on many levels.

Chris Pfeiffer • Dec 4, 2015 at 7:28 am

Nice job on the article and infographic Kaitlin.

Stephanie Catalini • Dec 3, 2015 at 8:19 pm

Very insightful article!