Not ‘crossed out

Nervous was an understatement. Alex Beilman was more than nervous. She was not emotionally ready to hear that her dreams of playing college lacrosse were shattered. Her parents tried to reassure her. Despite their calming influence, she was anxious. She dialed the phone and prepared to tell her story –

April 25, 2014

“I was really bad back then. Really flimsy,” she recalled with a laugh.

Lacrosse is a big part of Beilman’s life, but she didn’t actually start playing until she was in seventh grade. Before that, when she was in fourth grade, she started playing basketball. It used to be her favorite sport.

In addition to playing for Glen Rock’s travel team and recreational basketball league, she played AAU (Amateur Athletic Union) basketball. She went on to be a major player for the middle school basketball team. She was unique since she is left-handed, which gave her an advantage against her right-handed competition.

Beilman did a lot of training for basketball every day, and, in the summers, she went to a great deal of camps.

Outside of sports, Beilman did a little bit of everything. She loved art, dancing, and playing the piano and the violin. Even so, sports took priority over those hobbies.

When she started playing lacrosse in 2009, she fell in love with it, and it quickly became her favorite sport, even surpassing basketball.Still, she loved basketball, and continued to play all through the winter.

Then eighth grade came around. Like some of her classmates, Beilman thought about the possibility of going to a private high school instead of Glen Rock High School. She only considered it briefly. If she went, it would be for the education, not for the sports teams. Overall, she decided that she would stay in Glen Rock for high school.

In the interim, she was looking forward to eighth grade. In basketball, she would be a leader – one of the older kids. Things were looking good going into the season.

October 25, 2009. This was the day that things took a nasty turn for Alex Beilman.

Funny enough, it was the day before her fourteenth birthday. She was playing in an AAU basketball game. She was driving down the lane.

As she begins to explain what happened next, her expression becomes more serious and resigned.

The defender from the other team was riding her hip, and there was another close behind her, both trying to prevent her from driving to the basket. The girl behind her stuck out her leg, which got caught between Alex’s legs

Beilman’s left knee twisted unnaturally. She fell to the floor—hard. She didn’t know it at the time, but the pain she was feeling was only the beginning of her troubles.

Alex Beilman had never before been seriously injured.

She went to the emergency room that night. There, the doctors told her that she probably just sprained her knee. But since Beilman’s mother works in physical therapy, and sees a lot of injuries, she was a little suspicious of this diagnosis.

A week after she hurt her knee, it was still bothersome and very swollen. Mrs. Beilman was still not convinced that it was just a sprain, so they went to a specialist. It was there that Beilman was informed that she had torn the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in her left knee.

“Hearing this was the end of the world to me,” Alex Bielman recalls. She spent the days following her diagnosis crying and thinking repeatedly, my life is over! She was finally in eighth grade, and was supposed to be a leader on the middle school basketball team. Now, she would be out of all sports for months.

She truly felt that everything she had worked for was ruined and that her life was over. Reflecting on those days, Beilman clarifies, “clearly it was not [the end of my life].”

Yet in that moment, it was hard for her to be positive. Eventually she got over it, and she decided to put her efforts into getting better and getting ready to return to sports.

With this injury, Beilman realized that she would need to work hard, and put in serious effort if she wanted to get better. She knew that it would not be easy, but she had to believe that it would be worth it.

She was right about both things; it was hard to get through her injury, but it has definitely been worth it. It took her six months until she was able to return to sports. During those six months, she was never idle.

Her parents got her a toy basketball hoop that she could hang on her door. When she made the ball in, it would roll back to her. Beilman would sit in her room, shooting the ball over and over again, practicing her shots while she could not practice much else.

To keep her spirits up, Beilman’s mother would tell her inspirational quotes. Beilman still remembers them:

“It always seems impossible until it’s done.”

“You don’t have to be great to start, but you have to start to be great.”

“Life isn’t about waiting for the storm to pass. It’s about learning to dance in the rain.”

“I’m not saying it’s easy. I’m saying it’s worth it.”

“It’s not about how many times you’ve fallen; it’s about how many times you’ve gotten back up.”

“When you reach the end of your rope, tie a knot and hang on.”

“The best is yet to come.”

Outrunning her opponent, Alex Beilman breaks down the sideline.

The comeback

Beilman was ready. She had finally recovered from her ACL tear, and had the green light to return to sports. Her first game back was a tournament at Rutgers University. Everyone around her, including her parents, her coach, and her teammates were nervous. But Beilman was thrilled. It had been too long that she was cooped up, and she had been anticipating this moment for months.

When she finally stepped on the court, everyone held their breath. In the first play, she was running and tripped, sending a wave of fear through the crowd. Everyone was frozen at the sight of Beilman on the floor.

But Beilman just stood up, dusted herself off, and said, “Yep, I’m good!” This little incident made her realize she was going to have to work on her balance. But she was not shaken; she was ready to get back in the swing of things.

Taryn Tabano was sold from the first time she met Beilman. It was shortly after Beilman had healed from her injury, and she was weeks into her eighth grade lacrosse season. The then assistant varsity coach of Glen Rock High School’s girls’ lacrosse team, Taryn Tabano, was talking with the head coach, Karen Mackie, after a game.

Karen pointed out Beilman on the field, practicing her shots. She told Tabano of Beilman’s great talent, her commitment to the sport, and how she would be an incoming freshman the next year.

Beilman came off the field and was formally introduced to Tabano. The athlete explained that she had just finished a game against Ridgewood, and she had missed some right-handed shots, so she had been practicing taking shots right-handed for the past two hours.

“What an incredible young woman,” Tabano said. “I didn’t need to see her playing in a game, I didn’t need to see her running line drills; I just knew that second that she was going to be an impact player for Glen Rock High School.”

Tabano admired Beilman’s “sheer devotion to physically go out and practice that one thing… that she couldn’t rest until she got [it] out of her system.”

This is the same story that Tabano, now the girls’ head varsity coach, would tell a few years later to college lacrosse coaches when Beilman was being recruited.

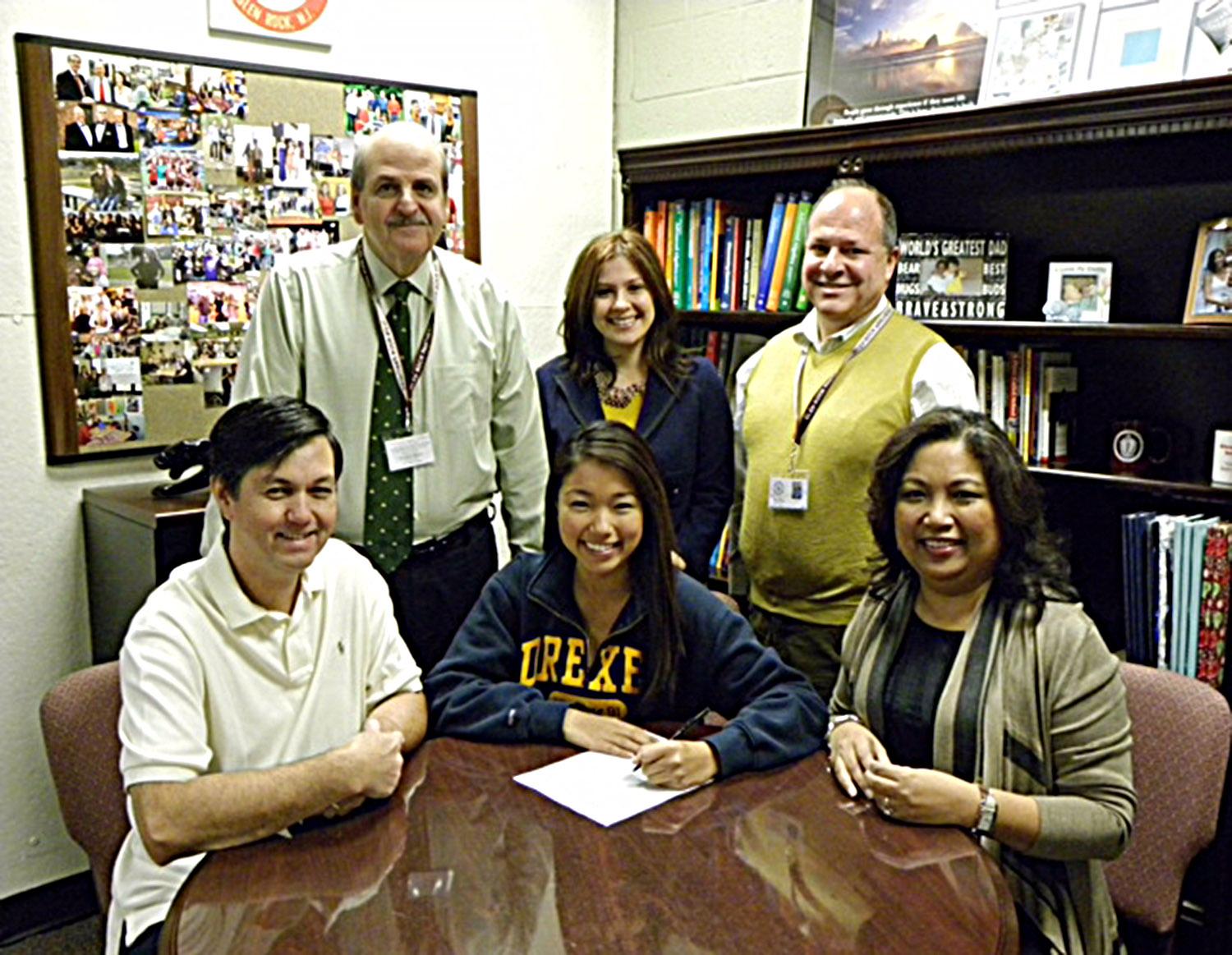

As a junior, Alex Beilman signs with Drexel University for the 2014-2015 school year.

Signing

Beilman’s freshman year in lacrosse, Glen Rock played some very difficult teams. According to Tabano, they were “playing programs like Mountain Lakes and Ridgewood… basically teams that don’t have a single player on the field that isn’t going to a top ten Division 1 program.” Glen Rock High School’s program, on the other hand, consisted mostly of underclassmen.

It was a difficult year for the program, but it turned out to be a winning season.

Although the season was tough for everyone, it was especially tough for Beilman. She had missed so much during her injury, and now she not only had to transition back to playing in general, but she also had to come back and be ready to play on a high school level. This was going to be hard, physically and mentally. But that would not stop Beilman. She just remembered one of the many inspirational quotes her mother had told her when she first tore her ACL: “The struggle you’re in today is developing the strength you need for tomorrow.”

In the summer, she played lacrosse for a club team called Steps Elite. She spent hours training, trying to get better.

And that’s exactly what she did.

Beilman’s sophomore lacrosse season was like something from a movie. Tabano remembers one particular instance that she considers to be Beilman’s break out game. It was a game against Indian Hills and Beilman was ‘on her game.’ She had half a dozen goals and a few assists as well. Her showing was so impressive that it prompted the Indian Hills coach to approach Tabano and ask, “Who is this girl? Where did you get her from?”

From then on, Beilman was a top player in the county. By the end of this break out season and in the summer following it, she realized that playing lacrosse at a higher level was a possibility. More than a possibility—it was likely. College coaches began to watch her at tournaments and even communicated with her over email.

She had inquiries from Boston University, Drexel, High Point, Muhlenberg, Quinnipiac, and Trinity. Beilman spoke to a lot of colleges overall. It was an exciting time for her and one that showed her what a bright future she could have.

Although in middle school Beilman had realized that she was not tall enough to play basketball at a higher level—she stands only 5’5”—and had written it off, she was discovering that lacrosse was a different story.

In fact, things were quite the opposite in lacrosse. “She uses her size to really manipulate space, which is so important as an attacker. And she has a great shot,” Tabano said.

As Beilman’s junior year began, she started to do more research and try to get a better idea of what she wanted to do. Midway through the year, she started to lean towards Drexel, not only because of the Division 1 lacrosse program, but also for the academics. The school has a great science program and, additionally, has its own medical school. Beilman found this very attractive, as she might want to go into the field of medicine.

The academics with the great lacrosse program make it “the best of both worlds” for Beilman. She loves the lacrosse coach and said that, when she visited, all of the girls on the team were very inviting. All of this was a perfect fit for Beilman and made her decision to commit easier.

It was a unique position for Beilman to be in; as a junior, she already knew where she would be attending college. While her classmates were worrying about SAT scores and college visits, Beilman had the opportunity to sit back and appreciate the fruits of her labor. This did not mean that she would take it easy for the next year and a half; it was not in Beilman’s character. She continued to work hard in sports and in school, as she had done all her life. She even earned the honor of being named an Academic All American.

At the end of her junior lacrosse season, she was been named as one of the captains for the Glen Rock High School 2014 girls’ lacrosse team.

Her peers and coaches describe her as a quiet, effective leader. Elise Doubet (‘14), who has been playing lacrosse with Beilman for years, said, “She brings everyone together. She always knows what to say.”

Tabano admires how Beilman leads by example. “She doesn’t lead in that vocal rah-rah way all the time; she’s always there to be uplifting and to use her voice to empower her teammates,” she said.

Calamity

As her junior year came to an end and her final year of high school was not so far away, Beilman had a lot to look forward to. She was set with her college decision, and ready to have a great senior year. She was even playing her final season of club lacrosse with Steps that summer.

Beilman knew that the last game of the season would be emotional, as it would be the first of many goodbyes she would have to go through in the coming year. It would mark the beginning of a year of changes.

But she did not know just how much her life would change after that game.

It was July 28th, and Beilman was in Virginia for the final game. Time was running out in the last quarter. She was so close to the end; so little time left.

And then it all happened so quickly.

Beilman was faking out a defender. As she turned back to go the other way, her right leg became stuck in the turf. It twisted, and she fell on it. She knew as soon as it happened that something was wrong.

She didn’t cry. She just sat there on the ground, thinking, this can’t possibly be happening again. She had much more going for her now – so much more to lose.

Although Beilman was convinced that the problem was with her ACL, the trainer at the game tested her and insisted that it was her hamstring. She could still walk, and it didn’t seem as badly injured as when she tore the ACL in her left knee. This, along with the fact that everyone was telling her not to worry, made Beilman believe that it was not as bad as she originally thought. She thought she would be fine.

But still, when she returned to New Jersey she went to get checked out. Beilman thought she had been through the worst when she tore her left ACL in eighth grade, and that she could handle whatever news she received. But when the doctor informed her that she had torn the ACL in her right knee, everything changed.

Questions sprang forward like attackers sprinting towards the net.

Would she still be on the team? Would they take away her scholarship? What would she do if the worst happened?

Beilman’s thoughts raced through her head nonstop. Her parents tried to comfort her and told her not to worry about what might happen, but rather to focus on getting better.

She couldn’t help it.

She had always heard stories of players who had committed to play a sport in college and were cut from the team when they got injured. She so wanted to be a Drexel Dragon and could not bear the thought of not being able to be a part of the team.

She had another surgery, this time on her right ACL. Two life-changing surgeries in four years is more than some people have to endure in a lifetime.

Only Alex Beilman had just turned 18.

Alex Beilman received word from her future coach at Drexel.

The phone call

When the head coach of the Drexel Women’s Lacrosse team, Hannah Rudloff, answered the phone, Beilman spoke quickly, trying to explain every detail as best she could

She hoped for the best. She was nervous. She was sure her heart was beating loud enough for the coach to hear it on the other end of the line. Her future was so uncertain, and it all would be revealed after this phone call.

Beilman finished her story and paused, waiting for the verdict. She will always remember the words she heard that day, and the effect they had on her.

“Alex, don’t worry. It happens,” said the coach. “We still love you, and you’re still a great player.”

Relief flooded through her immediately. She could hardly believe what she was hearing. It was everything she hoped for and more.

Nothing would change.

She would still be able to be a part of the team. She would not lose her scholarship. She would be okay. More than okay, she would be happy.

Now, the only thing that Beilman has to look forward to is getting healthy again. When someone asks her about the fact that she has torn both of her ACL’s, she just smiles and replies that “they match.”

She has accepted all that has happened to her in the past and has set her sights on the future. Since this is the second ACL injury Beilman has had, her doctors are more conservative with her rehabilitation. She has to be out of sports for eight months instead of six, so they can ensure that she has enough time to heal completely.

Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays are spent at physical therapy at Excel in Waldwick. On Tuesdays and Thursdays she does weight training, and goes to work as a shooter for Ginny Cappichioni, who is a goalie for the men’s national lacrosse team. Then on Saturdays, she goes with her mom to work and sets up exercises to do on the side.

She will not rest until she is healthy.

Although lacrosse will continue to be a big part of Beilman’s life, she is also very excited for the other reason that she will be attending school next year—to get an education. She is thinking of going into a pre-med track or possibly going into physical therapy like her mother. She is interested because of what happened to her, and she thinks that she might want to make a career out of her experience.

Looking to the future, Beilman thinks that she will either continue school after getting an undergraduate degree so that she can become a physical therapist, or she will go to medical school. “We’ll see where that takes me,” she said.

Like any incoming college freshman, Beilman is worried and excited for what is to come. College is an entirely different atmosphere than high school and will definitely take some adjusting. But she is excited to be independent.

“It’s really a true test of if I can manage school and lacrosse,” she said.

The transition to college level lacrosse will require a lot of work. This year, she will have to recover from her injury to get back to a high school level, and then she will have to get ready for a college level over the summer.

She said that all of the training that she has gone through in her whole lacrosse career is equal to the amount of training that she will have to do this summer alone.

Beilman is not scared. She has been through so much already, and can do anything she puts her mind to.

“She’s lost it before,” high school coach Taryn Tabano said, “and I think it’s the mental drive that gives her the ability to consistently become better.”

The test

On April 4, 2014 Beilman took her ‘back to sports test,’ which was required before she could return to play lacrosse for her senior season at Glen Rock.

Beilman went into this nerve-wracking day nervous yet confident that she could face whatever the results were. This test would be more strict than it had been for her first injury; she would have to show that she was strong enough, even with two ACL’s that had been torn.

Her knees were strong enough. But her hips were a different story.

In order to return, everything had to be working right. The physical therapist who administered the test left the decision on whether or not she could return to sports up to Beilman’s doctor.

After waiting almost a week for an answer, Beilman’s doctor gave her the bad news: she was not ready to return to sports.

She would need another month of recovery before the doctor would reconsider.

This was hard news to hear. And though Beilman was upset, she was not broken. She had been through worse, and she knew that she would just keep working until she was completely healed.

Just like her mother told her all those years ago, “Everything will be okay in the end. If it’s not okay, it’s not the end.”

It’s just beginning.